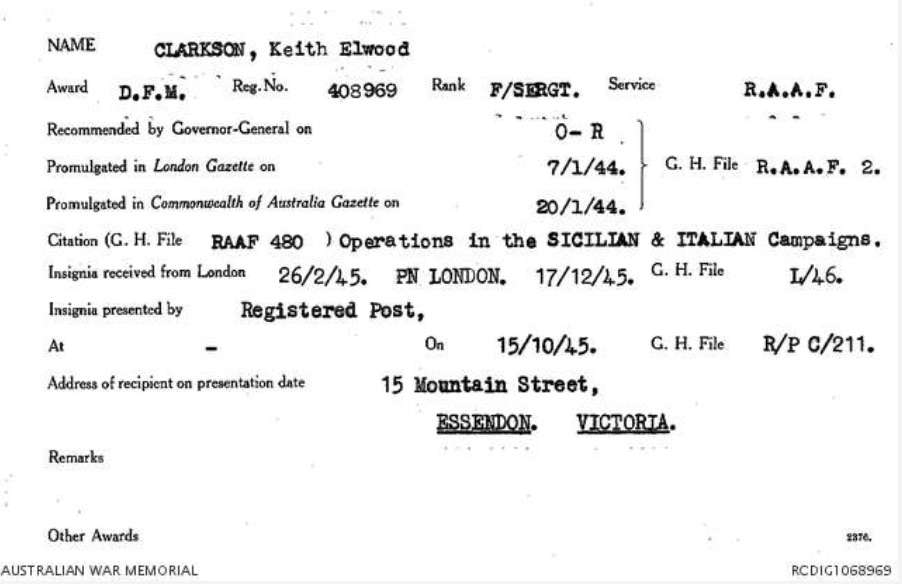

Lieutenant Keith Elwood (“Nails”) Clarkson DFM RAN was killed in action on 5 November 1951 whilst flying a Sea Fury in Korea. He was the Senior Pilot of 805 Squadron and was a highly experienced ex-RAAF pilot.

Clarkson had served with distinction in the second World War, including in an incident when he was shot down by an ME109 over Tunisia on 2 April 1943 (see his personal diary insert at the foot of this page). Following the war he joined the fledgling RAN Fleet Air Arm and was commissioned as a Lieutenant before being posted to 805 Squadron, which was part of the Sydney Carrier Air Group sent to Korea in 1951.

Clarkson was conducting a strafing dive on a truck that was probably part of a flak-trap, from which he did not recover. Aircraft circling the wreckage were twice hit by 20mm anti-aircraft fire. The 805 Squadron Diary entry for that day was as follows:

’52 Flight were first airborne and once more the Han River was the target. Troop concentrations were rocketed and strafed followed by an Armed Recce heading north from Packichan. it was during this recce that 52 leader was hit while making a strafing run on a possible truck at BT.670155. The aircraft rolled over on its back and dived into the ground, breaking into many pieces. No sign of life or of fluorescent panels were seen. One aircraft returned to the ship and the remaining two carried out Rescap over the area. Few enemy troops were seen and were strafed and some rockets put into a slit trench. Both aircraft were hit and soon had to land at Kimpo, being short on fuel.

The Diary would like to record the courage and determination of Lieut Keith Clarkson and say how much he was admired and respected by all pilots in the Group. His loss will be felt very deeply.’

Clarkson’s body was never recovered in Korea, but in a fitting tribute his medals were donated to the Fleet Air Arm Museum on Tuesday 20 November 2018 by Kenny Best, the nephew of Clarkson’s late sister, June Best. A Spitfire from Temora conducted a flyover in memory of the veteran. (Images South Coast Register)

Right: CAPT Darren Rae, CSO to COMFAA, accepts LEUT Clarkson’s medals on behalf of the Navy from Mr Kenny Best, his sister’s nephew. (Image South Coast Register). You can see the page about this presentation here.

Below: LEUT Keith Ellwood Clarkson, KIA 05 November 1951.

KEITH CLARKSON’S DIARY ENTRY

April 7, 1943

“Up to the second of April we were not very active but then we got some good weather and did a lot of flying. On the third of April we took a bunch of Mitchells over to bomb a ‘drome. We were flying in two lots of six; I was yellow two in the commanding officer’s section Flight Lieutenant Cox being my Number One. On the way back, Cox and I saw two ME109’s below so the two of us peeled off and went after them. The right hand one broke away and started climbing and we followed him up. Cox fired at him, but missed, and then I fired a short burst at about 250 yards with 10-20 deflection. I saw an explosion in front of his tailplane but had to leave off, as Cox went down in a hell of a dive to 10,000 foot. We climbed back to about 13,000 foot and saw two or three 109’s kicking about. We were all by ourselves and the rest of the squadron had lost us and our position was about 15 miles southwest of Medjez-el-Bab (Tunisia).

We had finished climbing and all of a sudden, I felt several terrific thuds, something hitting my leg and hand and the cockpit filled with smoke. The ailerons were jammed as all I could do was skid and jerk violently. He had another burst at the engine and then scrammed. It was one of the ME 109’s. In the first burst he blew quite a bit of my port aileron away and jammed my controls, blew most of the hood off, put a cannon shell just down by the side of the seat, and another bullet hit the throttle quadrant, busting it up. In the second burst he hit my pitch mechanism and put a couple of holes in the prop. After the second attack the prop went into fully coarse and within a few seconds the engine packed up. Fortunately I was at a good height and was able to glide for a few miles over our lines. I decided to bail out as it is very rugged country and no places for a forced landing. I glided down to 7-8000 feet, undid my harness, took off my helmet, trimmed it to fly as near to straight and level as it would and started crawling over the side. I got halfway out when it went into a nosedive practically straight down. My left leg was stuck in the cockpit and I couldn’t get it out, so I grabbed hold of the trailing edge of the wing and pulled like the devil and after what seemed like eternity my leg came out and I went whizzing through the air, spinning like a top. I jerked the ripcord and the chute opened and there I was about 800ft up, so I must have got out of the plane at about 1000ft. Lucky me. Just as the chute opened I heard an explosion and the plane had hit the ground and was burning fiercely. I was coming down into a deep valley and the wind was blowing me backwards against the side of the hill so I had to turn the chute around, I touched down very lightly in my stockinged feet and released the harness. As I didn’t know exactly where I was, I thought I’d better walk as far west as possible as there may have been some Jerries about, but some Arabs came along and they were friendly. They said in French that the British army was just over the hill and one of them gave me his sandals to walk in.

A couple of them carried the chute and in short time, three RAMC officers came along. I got to the top of the hill and from there rode about three miles to Thilbar where the RAMC are stationed in the monastery.

They operated on my leg to remove splinters and cleaned up my hand and I slept there the night. In the morning Mr Cox came up in the jeep and I went back to the drome.”