A British Air Force Officer, Sir Frank Whittle – was credited with single-handedly inventing the turbojet engine with the prototype running in 1937. This spurred British Government interest, and a jet engine of his design was fitted to a specially modified Gloster E.2829 (Meteor) airframe, with the maiden flight taking place in May of 1941. It delivered a modest 1,240lb of thrust but brought England into the jet age.

A British Air Force Officer, Sir Frank Whittle – was credited with single-handedly inventing the turbojet engine with the prototype running in 1937. This spurred British Government interest, and a jet engine of his design was fitted to a specially modified Gloster E.2829 (Meteor) airframe, with the maiden flight taking place in May of 1941. It delivered a modest 1,240lb of thrust but brought England into the jet age.

Work on the Vampire also began in 1941 by the De Havilland Aircraft Company. It already had critical success with the Mosquito, built mostly of wood due to the shortage of metal in wartime, and the same technique was employed with the Vampire’s fuselage. The design featured twin booms for a very specific reason: unlike the Meteor, which had two engines, De Havilland wanted only one to make it lighter and consume less fuel – but the modest engine performance of the day required a short tailpipe. The engine was therefore mounted at the back of the fuselage, and the twin booms provided support for the tail and kept it out of the way of the thrust. The Vampire was therefore the first operational jet fighter with one engine, and entered service with the RAF in 1946.

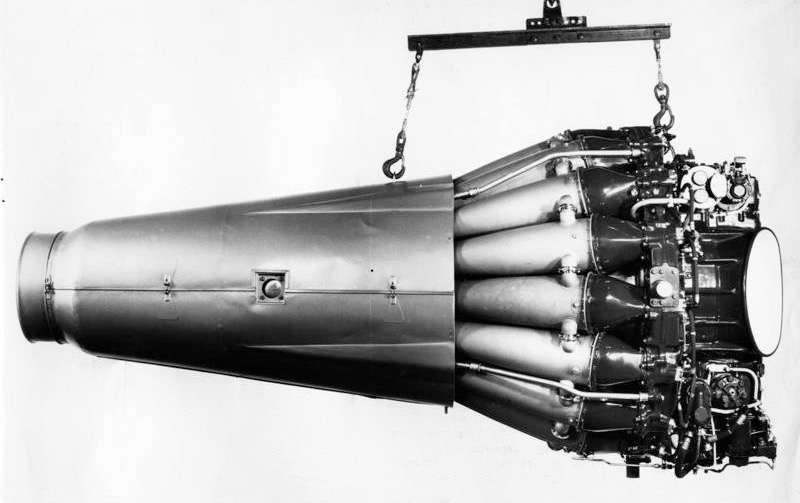

Above left. The first Vampire single seater (Wikipedia). By 1950 a training version of the aircraft had been developed. By then de Havilland had bought the company that manufactured the engine (the Halford H1). Right: Compared to Whittle designs, the H-1 was “cleaned up” in that it used a single-sided compressor with the inlet at the front, and a “straight through” layout with the combustion chambers exhausting straight onto the turbine. It was rebadged as the De Havilland Goblin. (Walsh Photo Collection).

The first five Vampire Trainers in the RAN were T.34 models built under licence by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation. They were similar to the T.33s the RAAF had bought, but ‘navalised’. Fitted with Goblin 35 engines – by this time capable of delivering 3,500 lb of thrust – they had framed ‘birdcage’ canopies, no ejection seats, and original tail fins without curved fairings. Left: The first RAN Vampire T.34 (A79-837) being accepted at DH Bankstown

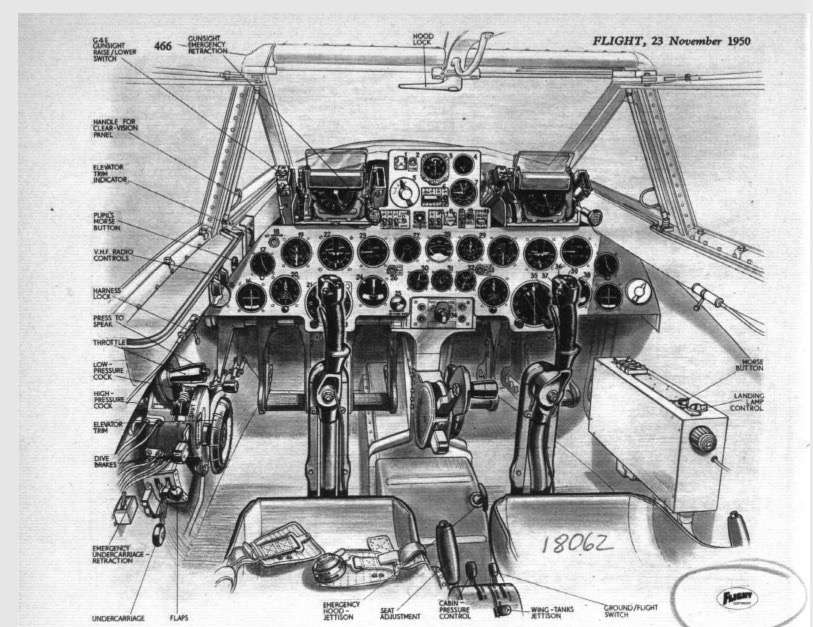

Right: ‘Flight’ magazine, a prominent aviation publication of the time, gave the Vampire much coverage – it was, after all, the first wooden jet fighter of its time. The magazine also heralded the twin-seat trainer, with this 1950 schematic captioned: ‘This view of the cockpit from the pupil’s seat makes clearly apparent the neatness and convenience of the whole layout’.

Alas, this could not be said of the RAN Vampires, which had a mish-mash of at least three layouts that made instructing somewhat challenging. An example of the poor cockpit ergonomics was the position of the single Artificial Horizon (AI), which required the instructor to lean over the student to see properly. The impracticability of this can be judged by the photo below left, showing just how cosy the seating was with two pilots. This prompted a modification to least one Vampire (below right) to fit two AIs (one for each seat) where the gunsights would have been positioned had the RAN ever fitted them.

The first five Vampire Trainers were built at the De Havilland Australia (DHA) Bankstown works, near Sydney NSW, who was producing licence-built Vampire T.33 trainers for the RAAF. These were T.34 models (serial numbers A79-837 to 841), which were delivered in 1954. Underwing drop tanks could be fitted, but no weapons were carried – the dummy 20mm cannons installed in the T.34s were for ballast only. Below Left. Not a very good quality image, but its the only photo we’ve seen of all five Bankstown built Vampires airborne at the same time. Within fourteen months two of them had been lost to separate accidents. (ADF Serials).

Below. Unsurprisingly, the Vampire had its share of handling accidents, such as the one below which put the aircraft out of action for about ten days. In this case the pilot selected the undercarriage rather than flaps up during a touch and go (the two levers were adjacent to one another near the throttle quadrant).

Over its life, four of the ten RAN Vampire airframes were destroyed: A79- 839 (fatal) in August 1956; A79-841 (fatal) in October 1956, A79-837 (fatal) in October 1967 and N6-838 (critical) in May of 1969. Fleet Air Arm members can access the FAAA Accident database here to view more details of these and other events.

Left. Anyone who served at NAS Nowra up to about the 90s will remember this scene, with the old control tower and this hardstanding to its east. Vampires served at Nowra from 1954 to 1970 and Gannets from 1956 to 1967, so there was plenty of time for photos such as this that showed both aircraft types. Missing from the image is a Sea Venom, which was bought at the same time as the Gannets and was the mainstay fighter of the Fleet Air Arm – and the reason the Vampire trainers were bought.

Below. In their seventeen years of service, the Vampires would have been a familiar sight around the airfield. Here are a couple of shots of refuelling. The open nose bay in the left hand image contained avionics.

Below: Another handling accident, this time in August 1959 when the pilot, Lieutenant Rowe, misread the Air Speed Indicator and aborted a take off. The aircraft left the runway and came to rest on the upwind end of runway 21. Both occupants were uninjured. The observer aboard, Lieutenant Ted Kennell, was to lose his life seven years later in a Sea Venom accident.

Above Left. In a role never played in the Royal Australian Navy, these Sea Vampires await launch from an RN carrier. The RAN deployed Sea Venoms at sea, using the Vampires purely in a training role. Above Right. Vampires lined up on the hardstanding at Nowra, in the days when fixed wing ruled the Fleet Air Arm.

By 1970 the Vampires’ 16 years of service were done, and they were phased out in place of the Macchi trainer. The photo left shows one of the surviving six ex-RAN Vampires, (N6-840) in a paddock – the last reported owner was Steven Demannuele but the current location of the aircraft and its status is not known. Of the remainder, one is in the Fleet Air Arm Museum at Nowra (720); one in the private Camden Museum (101); one in the Bankstown Museum (167), one reported as being in South Africa (766) and one unknown (842) but last known as being in Adelaide in 2002, possibly in pieces. The survival rate of six out of ten (we lost four in crashes) is still remarkable as none were scrapped, as for many other aircraft types. None, however, are flying.