For Mystery Photo number 30 the Webmaster asked readers if they could advise:

-

Where is the place in the photo, and

-

What is happening there, and why?

There was only one correct answer, from Kim Dunstan.

Sailors from HMAS Melbourne prepare explosives to destroy the old aircraft. Image via Max Speedy.

The photograph was kindly provided by Max Speedy, who also furnished the following story attached to it:

In February 1975 HMAS Melbourne was on her way to Hawaii for RIMPAC ’75, when one of her Tracker aircraft spotted a downed light aircraft on the very remote and very small Matthew Island somewhere near Noumea. Whilst they weren’t sure, no one could be seen at the site but subsequent checking with (then) French authorities assured the ship the crew had been rescued many months previously.

With RIMPAC over and Melbourne on the way home to Sydney in April, one 817 Squadron Wessex picked up a M. Martinet from the back of a tiny French minesweeper, and another brought a team from Melbourne with the aim of recovering the aircraft back to the ship. In the event this task was not feasible and given the time available, it was decided to remove the engine and destroy the aircraft to prevent someone else risking themselves in another rescue attempt. All well and good and the engine and its owner M. Martinet came back to the carrier and all returned to Sydney.

So how did the aircraft get there in the first place? A long and involved story.

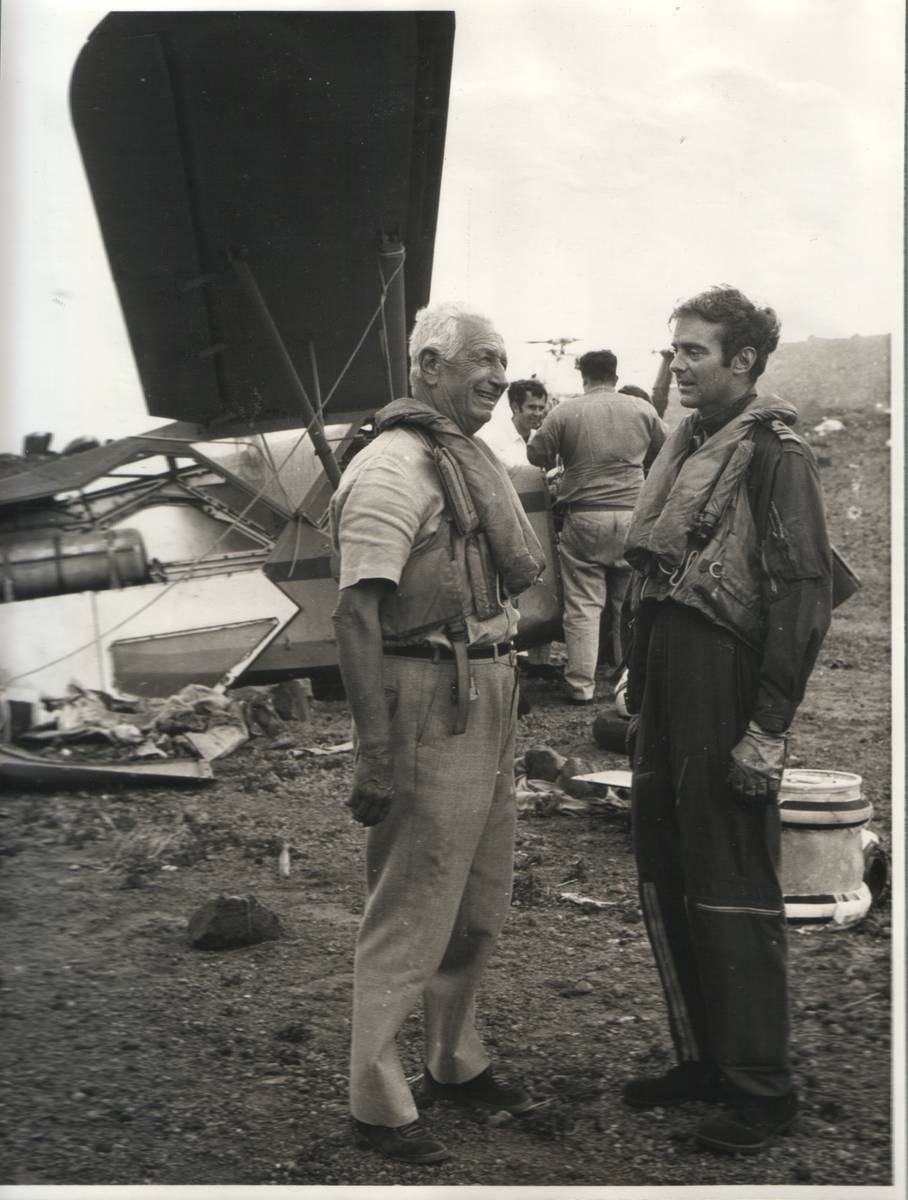

Left: M. Martinet and LCDR Terry Pennington, CO 817 Squadron, with the wrecked aircraft in the background. Image via Max Speedy.

Martinet had a vintage 2 seater Korean War era aircraft which had room for one litter patient lying in the fuselage behind the pilot and which he now used for supplies. The ‘supplies’ were generally a case or two of Champagne and fishing rods. He spent his time flying around the many islands in the area, where he would land on a suitable beach and stay there until the fish didn’t bite or the wine ran out. He had French Caledonia’s first Pilot’s Licence and had been doing this for many years. He’d even flown his plane to Paris for one of the 14th July Bastille Day celebrations, and a stamp to record the epic journey issued in his name.

Being relatively cautious, he had reconnoitred Matthew Island some time previously – it was then and still is just two volcanoes that have sprouted from the ocean deep, joined up and created a runway of sorts in between. With a chase aircraft just for comfort’s sake, he made his approach on this day and as he said, just as he closed the throttle to touch down, the stones that he thought littered the ‘runway’ turned out to be boulders and he smashed off a main wheel and broke the propeller. He and his new wife on her first trip with him escaped unhurt, radioed to the accompanying plane that all would be well and please get a new wheel and propeller and we will be fine for three weeks.

The accompanying plane returned a week or so later and told him the spares couldn’t be had in less than six weeks. A ship passing by picked him and his wife up with a life raft which it did with some difficulty.

So safely back in Noumea, M. Martinet finds another aircraft, a crew, his spares and an engineer to fly back out to repair his original aircraft. Now as all good aviators will know, the Inter Tropics Convergence Zone around the Equator travelling north and south with the sun can bring some very dark and stormy weather. It had more or less gone north of Noumea sufficiently for our team to fly off to fix the aeroplane and off they went. But the fickle finger of fate played her next card – our aviators flew into rain, flog and storm and got lost – so much so that they even ran out of radio contact with Noumea.

The next thing they ran out of was fuel and gliding to an uncertain ocean below managed to land safely enough for all to climb into their life raft where they spent the next 48 hours until being picked up by a French minesweeper. Exit the second aircraft.

Some 18 months later, HMAS Melbourne and her Trackers and Wessex came on the scene.

Below. Mr Martinet’s aircraft with the Wessex in the background. The quality of the ‘runway’ he chose to land on can be clearly seen. Image via Max Speedy.

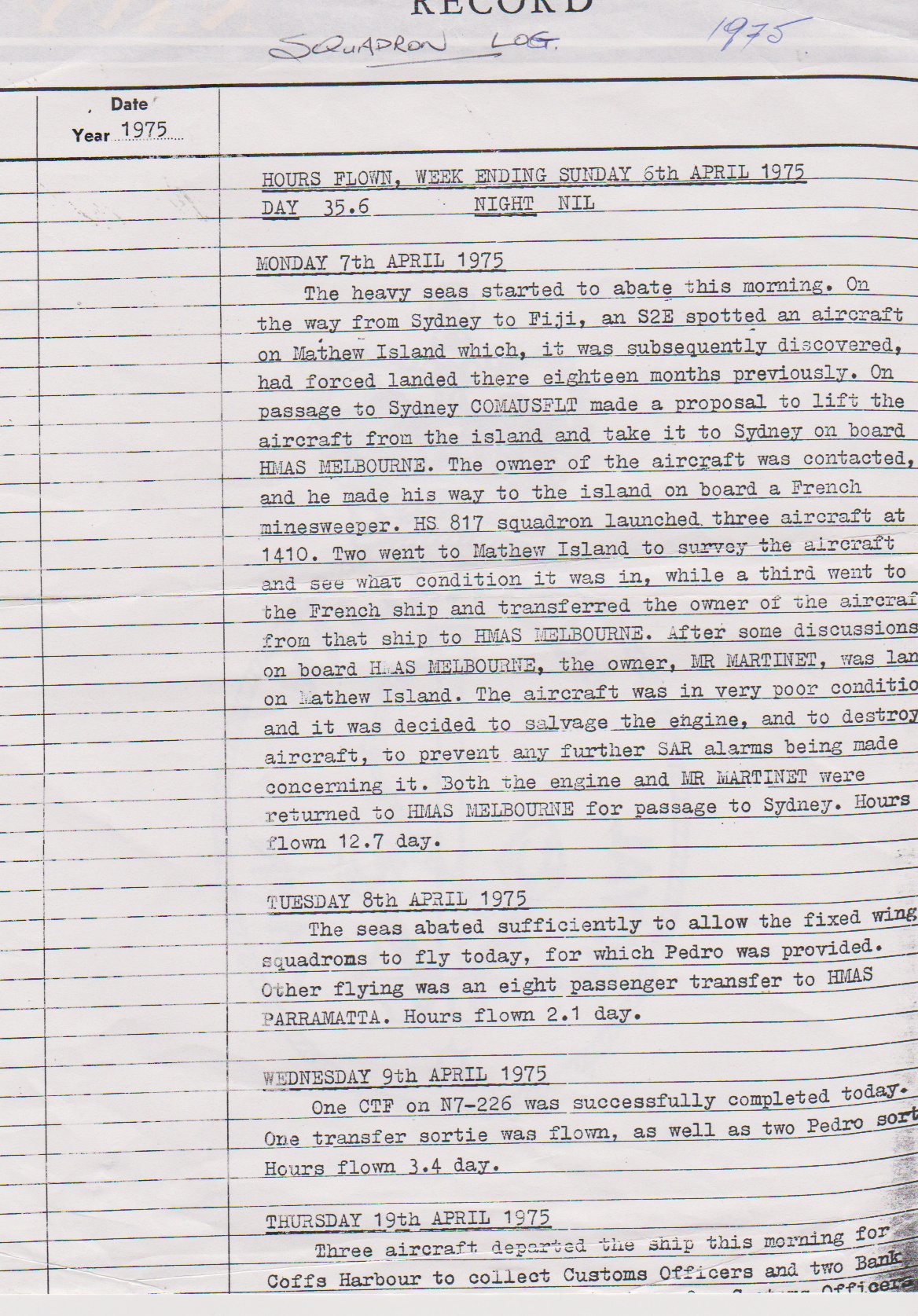

Below: An image of HS817 Squadron Diary, referencing the ‘rescue’ of the aircraft, and a further photograph of a Wessex lifting the engine clear of the wreckage.

After much work by Max Speedy and Kim Dunstan, together with the assistance of the ‘Aeroclub Caledonian Henri Martinet’, the mishap aircraft has been identified as a Stinson L-5B ‘Sentinel’. This model was capable of carrying a stretcher (or cases of champagne, depending on the circumstances). (Image on the left courtesy of Robert Frola)