1947-1950

Above. Having been transported to Australia on the new carrier, a cocooned Firefly is ferried ashore for transport to NAS Nowra, May 1949. Fifty-four aircraft were taken ashore and then transported by road to HMAS Albatross, which was still very much under construction at the time. Most of the aircrew and their families lived in caravans at the Nowra showgrounds, which had been extended with large packing cases used to ship wartime Spitfires to Australia.

Above. Having been transported to Australia on the new carrier, a cocooned Firefly is ferried ashore for transport to NAS Nowra, May 1949. Fifty-four aircraft were taken ashore and then transported by road to HMAS Albatross, which was still very much under construction at the time. Most of the aircrew and their families lived in caravans at the Nowra showgrounds, which had been extended with large packing cases used to ship wartime Spitfires to Australia.

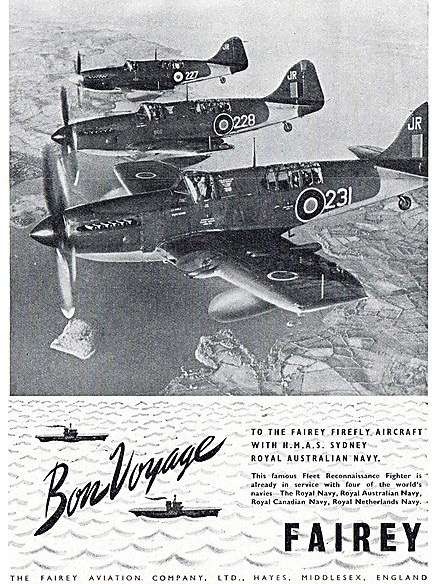

Above, Far Left: A 1947 newspaper article announces the acquisition of an RAN Aircraft Carrier. The keel of HMS Terrible was laid down in Devonport dockyard in April 1943 and she was launched some 18 months later. She was one of six Majestic Class carriers whose construction was halted at the end of WWII. In 1947 the Australian Government decided to acquire two of the class and work on ‘Terrible’ subsequently resumed.

Above, Centre: A Fairey Aviation advert from 1948, probably about the time the carrier was handed over to Australia and renamed Sydney. The photograph was taken on 03 December 1948 and shows three Eglington based aircraft.

Above: Firefly SLV Argus: Obviously a posed publicity shot but we have some details courtesy of the late Ian Ferguson. The fellow standing beside the cockpit on the starboard side (just visible) is ‘Horse’ Kennedy RN A/E (Aircraft Engines), so named because of his distinctive jaw. The pilot is the CO of 816 (name unknown), and behind him is the young J.D. Goble. The fellow kneeling on the wing facing outboard is Phil Harris (RN SAM), and standing beside him holding the ammunition is ( name forgotten RN AA3). The CPO standing with the white cap is George Dash. Kneeling just outboard of the port undercarriage is John Elliot, and holding the motor is an Aircraft Handler (name forgotten) who was recruited on the spot and given a white cap to make him an instant armourer. Ian said the ship was in Jervis Bay in the 1950s and the rocket heads were 60 lb HE. (Photo SLV Argus collection).

Left: HMAS Sydney departing Sydney harbour with a contingent of Fireflies aboard, 30 August 1952. (RAN image). The ship was bound for Monte Bello Atomic Bomb tests.

Below: One of the early accidents. Firefly VG998 (238/K) after a slow approach during arrester gear trials on HMAS Sydney on 08 February 1949. The undercarriage and hook were removed on the round down, and the aircraft skidded into the barrier on its belly although the fuselage caught on No 8 wire. (Lt D. Buchanan, RAN). It was classified as a write off. (Image: I. Ladler)

1950-1952 The Korean Conflict

Above: “Taffy” Morris and Col Champ standing beside their Firefly, which is primed for a strike with 500 lb bombs and 20mm cannon. (RAN image). Below left: a Firefly operating aboard HMAS Sydney during the Korean conflict. (George Trussell collection, Air Britain Photo Images). Below right. A great shot of a Firefly airborne. This particular aircraft survived its service life and was sold in 1966 to an RN officer, to make its way back to the UK aboard HMS Victorious. It was eventually restored to flying status and served with the RN Historic Flight for eleven years before crashing into a wheat field near Duxton during a solo display. Lt Cdr W. Murton and Mr N. Rix both lost their lives in the tragedy. The wreckage was returned to Yeovilton by road but it is not known what happened to it. (History courtesy of ADF Serials, Image scanned from RAN Historic Archive).

Above: “Taffy” Morris and Col Champ standing beside their Firefly, which is primed for a strike with 500 lb bombs and 20mm cannon. (RAN image). Below left: a Firefly operating aboard HMAS Sydney during the Korean conflict. (George Trussell collection, Air Britain Photo Images). Below right. A great shot of a Firefly airborne. This particular aircraft survived its service life and was sold in 1966 to an RN officer, to make its way back to the UK aboard HMS Victorious. It was eventually restored to flying status and served with the RN Historic Flight for eleven years before crashing into a wheat field near Duxton during a solo display. Lt Cdr W. Murton and Mr N. Rix both lost their lives in the tragedy. The wreckage was returned to Yeovilton by road but it is not known what happened to it. (History courtesy of ADF Serials, Image scanned from RAN Historic Archive).

Left: Not a particularly good quality image, but it is one of the few we have found that shows a Firefly with a full load of 16 RPs. These are concrete practice heads, probably during a work up serial out of Hervey Bay in QLD. Fireflies only carried 16 HE rockets very rarely, due to weight considerations.

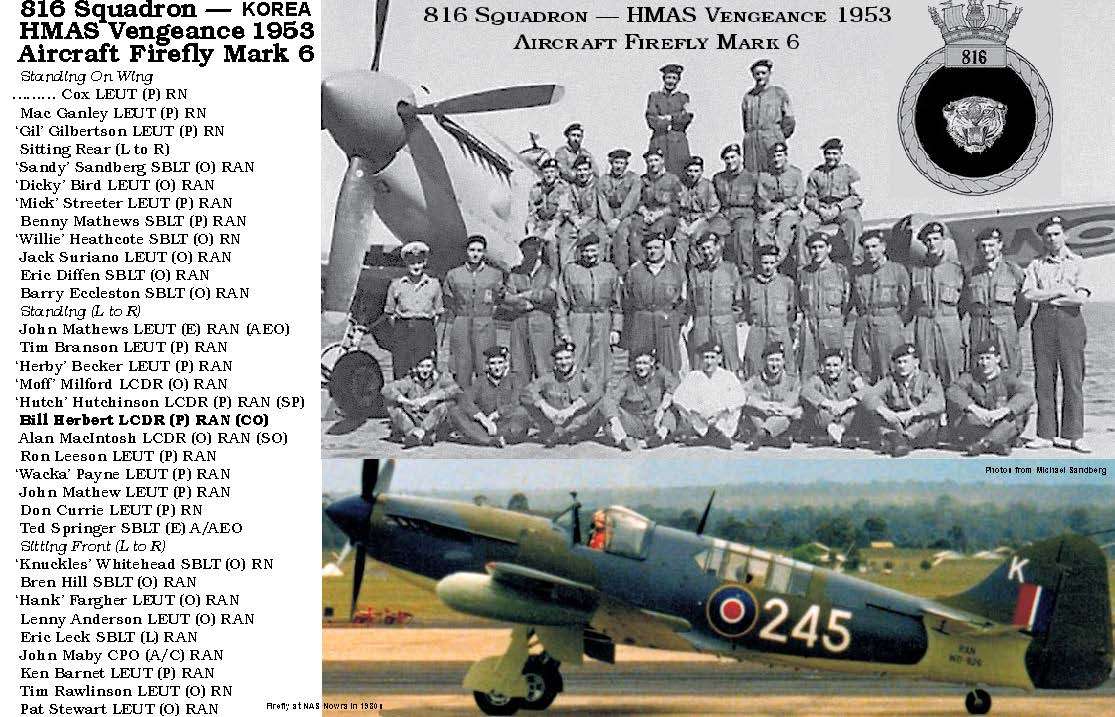

Below. 816 Squadron aircrew pose on their Firefly VI. The photograph is annotated ‘Korea’ but HMAS Vengeance never served in that theatre. Perhaps the photograph and its embedded text was taken when there was still an expectation that she would be deployed there.

Above. Image via Phil Thompson.

Left: Sydney riding out Typhoon Ruth on 14 October 1951 (AWM). The rough weather ruptured long range fuel tanks, allowing the ship’s ventilation system to circulate AVGAS fumes. A number of small fires broke out and it was fortunate that there was no major fire. On deck, thirteen aircraft (those that could not be squeezed into the hanger) were lashed down and the under-carriages of some aircraft collapsed. On the flight-deck aircraft handlers worked ceaselessly secured to lifelines to secure the wire lashings. A Firefly was washed overboard in the worst of the weather, with the typhoon reaching between force 12 and 13 and winds in excess of 70 knots. Twelve other ships were wrecked by the storm. When the storm moved north Sydney returned to Sasebo, arriving the following day (on 15th October). There she exchanged her damaged aircraft for replacements from Unicorn. Photo via Phil Thompson. Below. Further images of Ruth and damage to aircraft (RAN images).

Below: A slight delay in the launching sequence has this Firefly idling on the catapult with a 500lb bomb under its starboard wing. Note the USN Sikorsky HO3S-1 helicopter hovering in the ‘plane guard’ position, ready to effect a rescue should there be a mishap on launch. This helicopter type was used in the extraordinary rescue of MacMillan and Hancox, which you can read about here.

General Photos

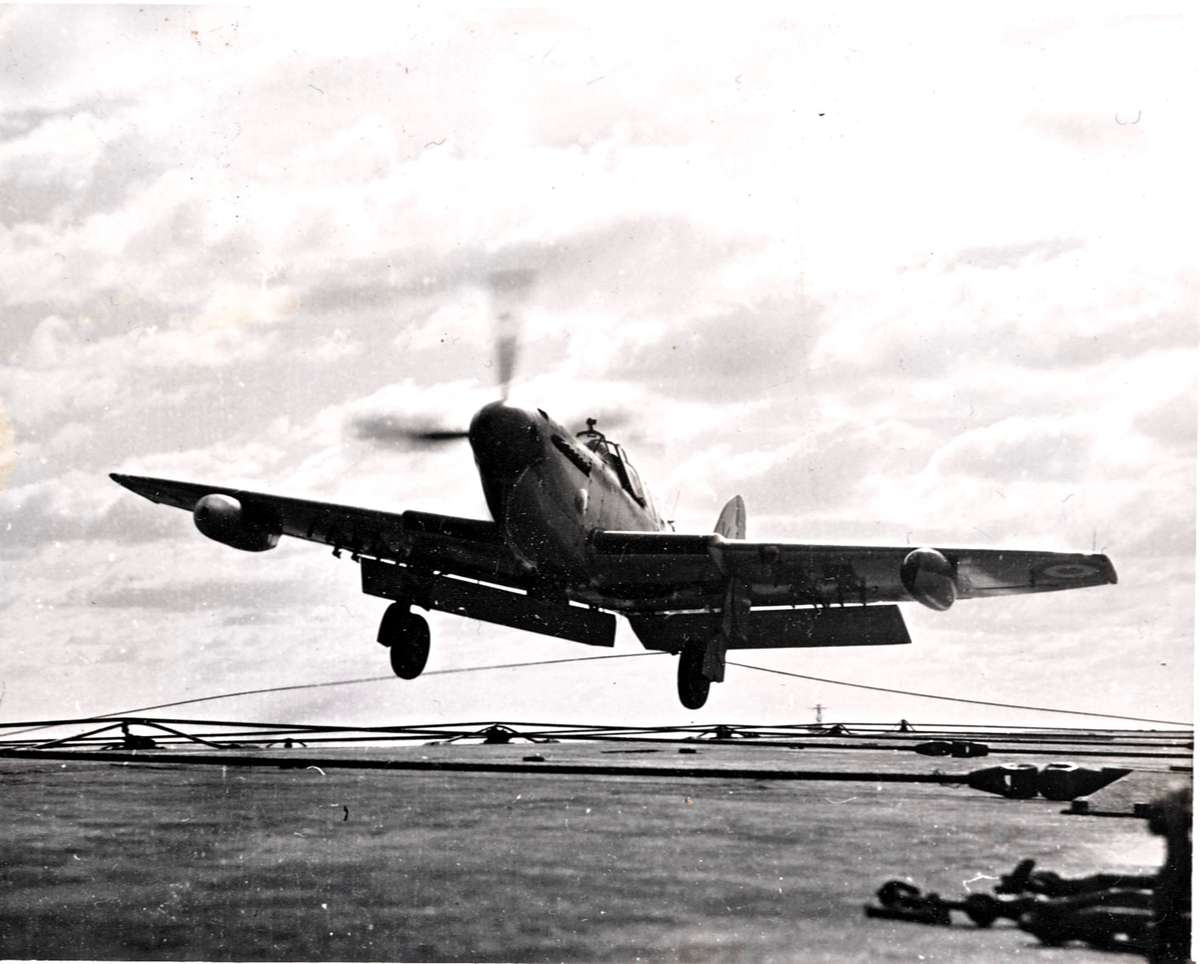

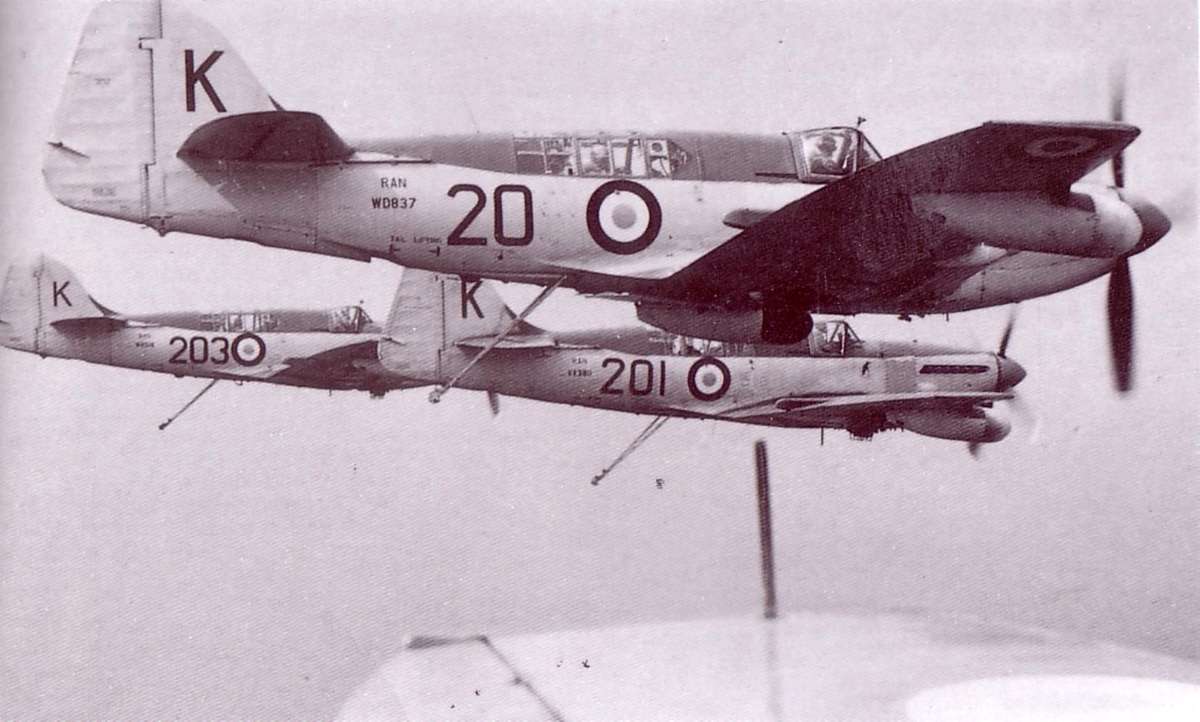

Above: A picture tells a thousand words. This one shows a flight of three 816 Squadron Fireflies preparing to launch off HMAS Sydney on a still morning (816 Squadron side numbers commenced with ’23’ whilst 817’s numbers were prefixed ’20’). The picture would have been taken prior to 2Jul56 as the Kangaroo emblem was introduced into the roundel after that date.

Above: A picture tells a thousand words. This one shows a flight of three 816 Squadron Fireflies preparing to launch off HMAS Sydney on a still morning (816 Squadron side numbers commenced with ’23’ whilst 817’s numbers were prefixed ’20’). The picture would have been taken prior to 2Jul56 as the Kangaroo emblem was introduced into the roundel after that date.

The lead aircraft is in the process of being catapulted – free takeoffs were routine prior to Korea, but with three Squadrons on board cat launches were necessary and stayed that way thereafter. The figure in white overalls was part of the catapult crew, positioned on the port side just aft of the catapult. He was a ship’s Engineering Officer and was responsible for all operations of the catapult including attaching the wire sling to the aircraft and catapult shuttle and the tail hold-down fitting.

The two handlers on the tail of the second aircraft would be ensuring it was correctly lined up with the catapult once it was moved forward into position. Note the tailwheel arm to assist them.

The three people forward of the second aircraft would be the first Flight Deck Officer, 2nd Flight Deck Chief Petty Officer handler, and 3rd Flight Deck Director who received the aircraft from the number 2.

Fly 1 can be seen on the right of the photograph. The person pictured would certainly be Commander Air. Beneath him (the vertical rectangular box) is the status lights Red, Green, Amber. CMDR(A) was ultimately responsible for the deck and gave the Flight Deck Officer the OK to launch.

The group on the right of the deck (below Fly 1) are the handlers coming forward after disengaging from other aircraft heading to the Catapult. The Fire Party consisted of three handlers would would be fully dressed in their Fear Naught Suits (the only ones available at the time).

A normal day would start with the pipe Hands to Flying Stations. All handlers would muster abreast the Island and be detailed for their various duties. This would include Chock Men, two Hook Men, a Talker and a Teller. These men would work with the Batsman (Landing Control Officer) – one would advise him on the status of the incoming aircraft’s flaps, wheels and arrester hook; the other would advise the LCO when the Flight Deck was ready, including Arrester Barriers.

Depending on the operational requirement there could be as many as 21 aircraft in the first take off. This in itself required 42 Handlers and it was always a race to get to the nearest aircraft. Work at the rear of the park was unpopular as the combined prop wash was like a hurricane.

Of all the aircraft operated at the time the Firefly was the hardest from a handlers prospective, mostly due to the manual wing-fold requirement. Parking took at least fifteen men: ten on the folding A frames, two on the wing locking pins, two on the telescopic arms that held the wings from hitting the main fuselage and one on the tail arm.

Information: Norman Lee and Trevor Tite. Image: Courtesy of FAAM.

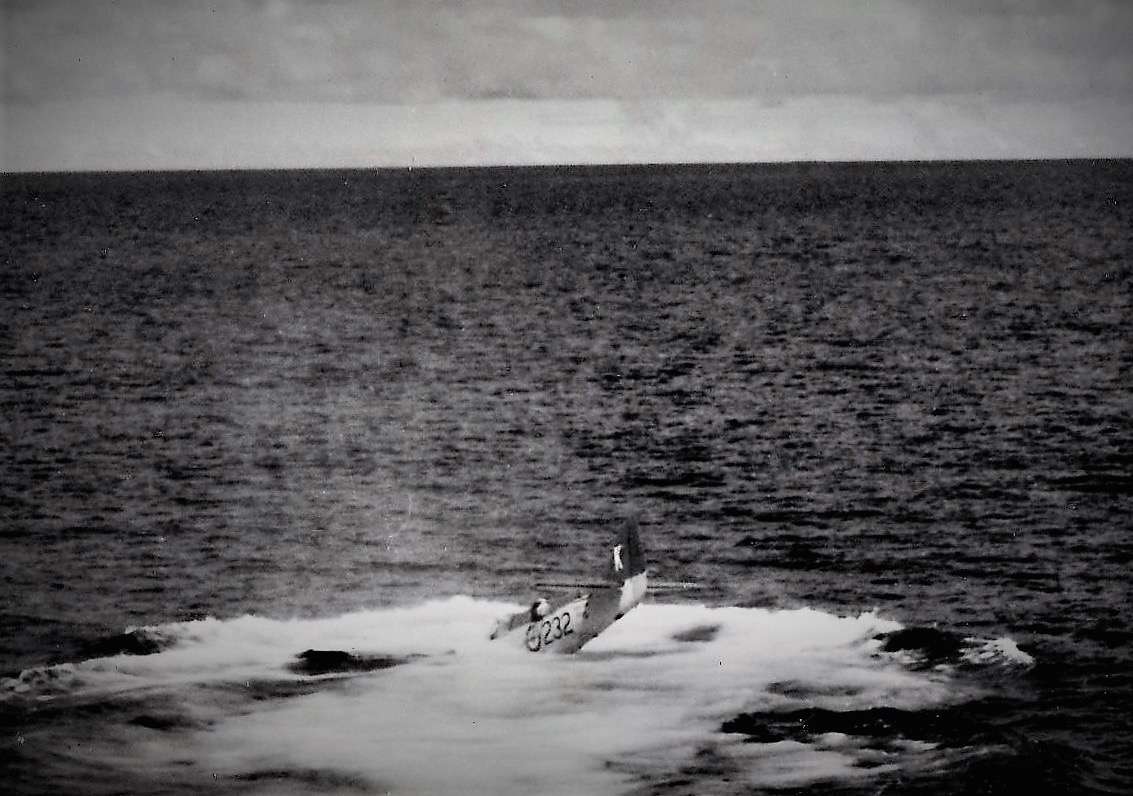

Above Left. The end of WB519. Sources differ on the account of this accident aboard Sydney on 10 June 1952. One report states the aircraft swung to starboard on take off and the starboard wing struck a fork lift truck. The pilot, LEUT A.B. Hayward, made a partially controlled ditching off the port bow.

Above Right. The history of Firefly airframes is littered with incidents where the aircraft ‘floated’ over wires. Most of them were arrested by the Barrier, but on 15 March 1949 Acting Lieutenant D. Buchanan floated VG973 over that too, to land in the deck park of HMAS Sydney. VH133 was severely damaged in the ensuring collision. Note handlers beating a hasty retreat (including ‘Tiny’ Davis about to enter a safety net).

Left. VH133 after the impact. The Observer was in the aircraft at the time but had bent forward to pick up some papers from the cockpit floor. It was obviously not his day to die! The aircraft was subsequently written off. (Image: Gordon Evans collection).

Below. Barriers were not particularly large, so it is easy to see how aircraft might occasionally ‘float’ over them. Here a Firefly approaches the two barriers raised to receive it.

Below [1]. A firefly on short finals to Sydney’s flight deck. The advent of the Mirror Landing Sight, which made its first appearance on HMAS Melbourne, allowed aircraft to make a constant attitude approach. Before that aircraft had to flare during the final moments of approach, which added to the difficulty. [2] An airborne shot of Fireflies with their hooks deployed, which was part of a check prior to landing. [3] Not much room inside! Space in Sydney’s hangar was always at a premium, as can be seen in this picture.

Above: A Firefly on the deck of HMAS Sydney. Note the unique wing folding mechanism that gave the aircraft an extraordinarily small footprint on deck or in the hangar. Wing folding was done manually up to the Mk V variant, which finally introduced power folding.

Above: A Firefly on the deck of HMAS Sydney. Note the unique wing folding mechanism that gave the aircraft an extraordinarily small footprint on deck or in the hangar. Wing folding was done manually up to the Mk V variant, which finally introduced power folding.

Above: A nice photograph of a pair of Fireflies tracking north, along the coast off Sydney…possibly on the way to embark on ‘mother’. This photograph was most likely taken either in ’51 or early ’52. Although most of the worlds Fireflies ended their lives on the scrapheap, these two were spared that fate. 234 (WD833) eventually made its way to the United States, where it is reportedly being returned to flying condition. 241 (WD840) was one of the few Fireflies to actually destroy one of its own kind, when it went through the barriers aboard HMAS Sydney in September 52 and struck WB338. It was later sold to a collector in Canada, who modified it to carry eight passengers. After various other homes it was last reported as being restored (again) to flying status by QG Aviation, Fort Colllin, Colorado. (History courtesy of ADF Serials).

Below: A training accident to Firefly VX379 on 11 January 1959, when LEUT Clarkson struck a boundary fence after stalling during ADDLs. The subsequent investigation blamed both the pilot and Deck Landing Control Officer for slow reactions to a rapidly developing situation. The aircraft was written off. (RAN image).

Below: A training accident to Firefly VX379 on 11 January 1959, when LEUT Clarkson struck a boundary fence after stalling during ADDLs. The subsequent investigation blamed both the pilot and Deck Landing Control Officer for slow reactions to a rapidly developing situation. The aircraft was written off. (RAN image).

Above: Richard Seaman’s dramatic shot of Firefly WB518, one of the last remaining types still flying. The ‘glasshouse’ Observers cockpit, squared-off wingtips and protruding wing-root radiator inlets gave a distinctive look. The last two features were introduced in the Mk IV version of the aircraft – the clipped wings giving a better rate of roll. The Mk IV update also included the more powerful Griffon 74 power plant and a four bladed propeller. (Photo copyright Richard Seaman). Like many restored vintage machines, it is not all it seems: the aircraft is actually an amalgamation of WD828 and WB518, both of which served in the RAN. The owner decided to use the serial number of the latter, as it had the lion’s share of the finished aircraft.

Left. A striking image of a restored Firefly bearing the black and white bars on the wings. This signified it was on operations with the United Nations. (Image courtesy of Stuart L. Robotham)

Below. One of the few (three?) Fireflies converted from Mk V to T.2 configuration by Fairey Aviation Bankstown. The most obvious change was the addition of a second pilots cockpit in place of the Observers, giving a curious humpback appearance. The number of 20mm cannon was reduced from four to two. The port wing fairing contained ASH radar and the starboard provided for additional fuel. Image via Jeff Chartier.

Below: A Firefly undergoing maintenance on the lines at Nowra, date unknown. The shot gives an idea of the complexity of the wing folding. (Image via Jeff Chartier).

Above Left. VX377 aboard HMAS Sydney with 817 Squadron, on 13 September 1954. On landing it had caught No.10 wire and entered the Barrier (Sub Lt D.J. Orr, RAN & Sub Lt W.T. Mulholland RAN). Because Sydney didn’t have an angled flight deck the Barrier was rigged for every landing, and catching 10 wire virtually guaranteed you would strike it (Image via Jeff Chartier). Above Right. One of the lucky ones. Firefly WD827 was spared the scrapyard and ended its days in the National Aviation Museum in Moorabbin, Vic. In this photograph it is probably at its interim resting place in Blacktown, having been sold to the Australian Air League in 1956. It rested there for 16 years before being acquired by the Museum. (Image via Jeff Chartier). Click on any image to enlarge it.

Below. A rare shot of three Firefly T.2 trainers in loose formation: from left to right VT440 (961); VT502 (963), and VX373 (963). The exact date of the photograph is not known, but it would have been some time after mid 1954, which is when VT502 (962) was converted to this role. None of the Australian T.2 Fireflies survived as they were all sold to scrap merchants. (RAN image via FAAM).

Below. The person who took this photograph is not known (image via Jeff Chartier), but it is likely he got the date wrong. Fireflies from 817 Squadron visited Home Island in the Cocos group on the morning of Saturday 04 April 1953, whilst HMAS Sydney was on route to the UK on the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation cruise. The aircraft reportedly delivered a consignment of beer which was exchanged for coconuts and other island specialties.

Below. When the Fireflies were replaced, a few were spared from the wrecker’s yard as they were employed as target towing aircraft. The four photographs below show this last, final role of this magnificent aircraft (click to enlarge). Even then, there was a final twist: in the final stages of the Firefly’s target towing duties, they ran out of cable cutters on the winch so the Observer was given a bread knife attached to a broom handle which was lowered through a hole in the cabin floor to cut the drogue webbing over the airfield.

Below: An ignominous ending. This surplus Firefly is being used for firefighter training at HMAS Penguin. Such aircraft would be ignited with trays of burning oil, which would then be swiftly extinguished. Image: RAN.

Note.

I wish to extend my grateful thanks to those who contributed images and information for this page. Some photographs have been obtained from anonymous libraries and their source cannot be determined. Others have been gleaned from the internet where there is no acknowledgement of their source. I extend my apologies to anyone who believes they have copyright, and invite them to contact me using the ‘Contact Us’ form below.

Marcus Peake

Webmaster December 2017

Magazine Article Read detailed magazine article on the Firefly.

Firefly Video Library