With HMAS Melbourne no longer available, the ‘rotary only’ RAN Fleet Air Arm had to face a new reality. It had previously operated on smaller ships from time to time, but only for very limited periods. It now had to learn how to do so for much longer periods – not as simple deployments, but as autonomous ‘Flights’ which were an integral part of the ship. Such Flights did not have the luxury of numbers, required reliable and nimble logistic support and demanded maintenance personnel who were trained and authorised to operate far from home for many months. It was a new concept that would take time to perfect.

The new FFGs were coming out of the United States, designed for helicopter operations – but the RAN lacked a suitable aircraft. Whilst Sea Kings could just squeeze onto the flight deck (above), they were too big for the hangar. So too, was the ageing Wessex. Eventually the FAA used AS350 Squirrels for the job – hardly a maritime helicopter but, in the event, they did an amazing job and taught the RAN much about small flights and how best to fully integrate them into the ship.

The US sourced Bendix AN/AQS-13A sonar (as used on the RAN Wessex Mk 31B) was installed. This allowed the transducer to be lowered to 450 feet rather than the 95 foot cable on the RN HAS.1. Of note, is that the cable hover mode on the RN version maintained a vertical transducer rather than the fixed cable location within the well in the helicopter deck used in the Mk 50. This sonar change allowed the RAN transducer to dip to 450 feet making better use of sonar conditions and layers, but at the expense of never knowing if the transducer was vertical, or not, making sonar beam performance somewhat of a lottery.

The sonar transducer’s range and performance was affected by variables such as water depth, salinity and temperature, and in particular by sea water ‘layers’ displaying different properties. As the sonar transducer (‘the ball’) could be raised or lowered, skilled operators could work the depth to get better results, but it has to be said that the active transducer was probably more of a deterrent than a finder. ASW was best done with more than one aircraft. A nimble submarine generally required at least two aircraft to track it, with one being vectored ahead to pick up a fleeing contact, and/or to prosecute it with weapons.

Above. With its heavy lift capacity and long endurance, the Sea King was soon being used for a myriad of tasks. Left: Practice torpedo recovery had always been a problem. The weapon was designed to come to the surface in a vertical position once expended, but getting it ashore was easier said than done. A TRV (Torpedo Recovery Vessel) operated out of HMAS Creswell, but man-handling the torpedo in even moderate seas was dangerous work. 817 Squadron designed a cage that was dropped over the nose of the weapon upon which it swung vertically to capture it for sling loading home. Centre. Helicopter In Flight Refuelling (HIFR) was a technique for topping up fuel tanks off a deck too small to land on, or in prohibitive sea states. Here a Sea King practices the evolution by winching up the hose and plugging it into the refuelling point just below the main cargo door. Right. Recovering a downed Squirrel – easier than trucking it through potentially rough country.

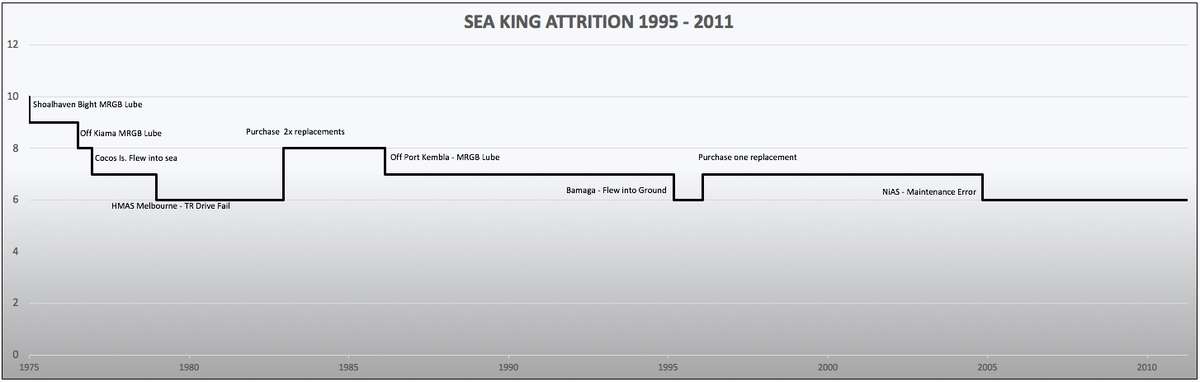

Above. By mid 1979 the RAN had lost four Sea Kings to accidents (click on graph to enlarge), and an order was placed for two refurbished replacements, which arrived in 1983. Two more aircraft were lost by ’95 and one more Sea King was acquired – an ex-RN machine. All in all, 13 were bought and seven lost to accidents.

Below. A closer look at the Helicopter In-Flight Refuelling (HIFR) system – a simple concept that involved lifting a hose from the ship’s deck with the rescue winch and then plugging the free end into the Sea King’s main refuelling point below the main door – all while the pilot formatted on the ship. It was practised occasionally but not often used in anger. (Navy Image).

Left. Photo shoot or photo shopped? We don’t know the origin of this photo or what this Sea King was doing so far from home – but its a nice image! The caption simply read ‘HS817 Sea King near Ayres Rock’, but it illustrates nicely the reach of the aircraft. Below. An 817 Sea King from an unusual angle, taken by a parachutist from the Parachute Training School (PTS) at HMAS Albatross. Jumping from helicopters was not usual practice but was done occasionally for the benefit of both aircrew and PTS training. (Click on image once or twice to progressively enlarge).

Left: HMAS Wollongong on the rocks at Gabo Island 31May85. In imminent danger of foundering, HS817 Squadron were called at short notice to fly flotation bags to the stricken vessel, to keep it afloat long enough for damage control and pumps to stem the flood. The vessel was eventually recovered and, after extensive repairs, returned to the Fleet the following year.

Above and left. The ability to quickly deploy an aircraft was a valuable asset, as shown by a situation in 1985 when the Antarctic supply ship, Nella Dan, became beset in thick pack ice. Unable to supply the Research base at Macquarie Island, Navy was called for assistance. Stalwart arrived at the Island in early December and spent some 60 hours there, during which her Sea King flew more than 29 hours, unloading 200 tons of cargo and making 115 personnel transfers. (Image above by Bob Reeves).

Left. The RAN’s 75th Anniversary in 1986 brought a new task for the Sea King – flying the flag! In the main picture an aircraft in special livery flies a mammoth White Ensign over the airfield at HMAS Albatross. The idea was replicated (inset) in later years whenever there was an opportunity.

Below (main picture). A stick of 4 Sea Kings on Operation BURSA. This required the Fleet Air Arm to provide air support for the SAS in the protection of oil rigs in the Bass Strait. The task was originally owned by 723 Squadron, but by 1986/7 its ageing Wessex helicopters were increasingly difficult to maintain and the task was handed to 817 and its Sea Kings. It was a huge burden, as it required regular deployments of multiple aircraft to RAAF East Sale in Victoria, as well as training for the SAS teams from Perth (WA) (inset). Over the period Jul 97 to Dec 89 the Squadron deployed six times to East Sale, before finally handing the task to Army and its more suitable Black Hawks. The full story of Operation Bursa, including Sea King involvement, can be read here.

Left. Navy News 22 July 1988 featured this photo of HMAS Stalwart’s aircraft, which stumbled across a life raft containing five seamen from a Kiwi fishing boat off the northern coast of NSW. They had been adrift for almost seven days after their vessel was swamped by heavy seas.

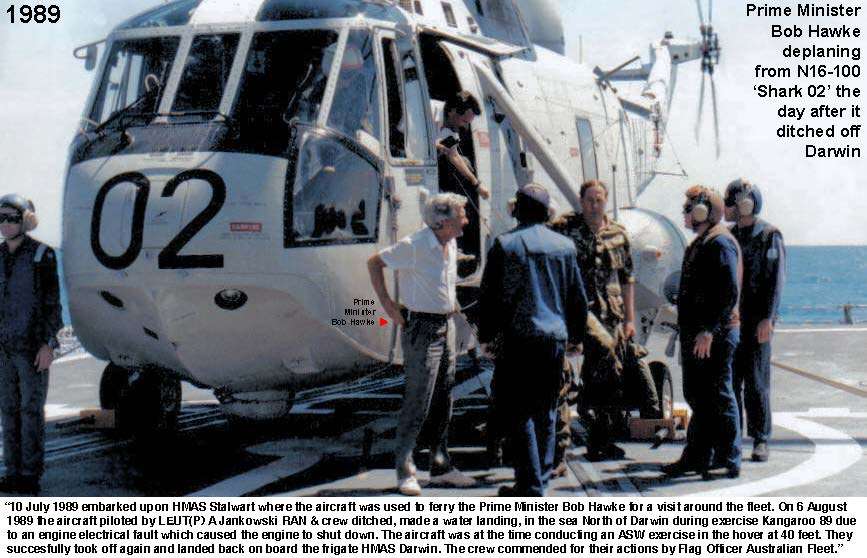

Sea Kings were increasingly being deployed aboard Stalwart and Tobruk, but the lack of suitable decks hampered wider deployments and the formation of true ‘Flights’. The shortage was so acute that, a year previously, a hasty wooden deck had to be built aboard HMAS Jervis Bay in order to accommodate a Sea King for ‘Operation Fiji Coup’, when it was feared expats may have had to be rescued from an unstable Fiji. The situation was exacerbated by the arrival of the first S70B Seahawks, which were progressively being accepted at Albatross, and which were also looking for deck time.

In the meantime, HS817 was carrying out annual deployments to work with the RAN Submarine Squadron. 817 Would conduct yearly exercises in the west and also out of RAAF East Sale. The West exercise was a large (for Australia) ASW Fleet exercise. The East Sale exercise with the Submarine workup training involving shallow water transits, peri-phots and opposed operations involved lots of good multi-aircraft dipping. Exercises to the West captured the interest of this cartoonist (left) who was amused by the fact that the Sea King’s significant downwash peppered ground crew with Tammar droppings when they landed on the football oval at HMAS Stirling. (Navy News 26 Aug 94). The Submarine Squadron felt the loss of the Sea King’s ASW role keenly, once it was removed.

Below. Operation ‘Solace’ in 1993 saw a Sea King deployed at short notice aboard HMAS Tobruk, in support of the United Task Force (UNITAF) in Somalia.

The RAN’s contribution to UNITAF comprised two ships: Tobruk and Jervis Bay, and was essentially about delivering supplies to Somalia’s starving population. It was not approved until 15Dec92, and frenetic activity was required to recall crews and load over 800 tons of freight. JB sailed from Sydney two days later and Tobruk, which required urgent engine repairs, on the 26th with an 817 SQN Sea King embarked. Below. Tobruk arrives in Mogadishu, and left, a view of the city from the rear cabin (AWM image).

Below Left. Tobruk’s Sea King carried a light machine gun in the cabin, possibly the first time one had been fitted in anger. There are no reports of it having to be used during the deployment, which ended in May of that year. Below Right. By 1995 the surviving Sea Kings of the original batch were 20 years old. A Life Of Type Extension (LOTE) program was progressively carried out, providing new Avionics and Radios, a new Radar, removal of the last of the sonar gear to give 18-seat troop capacity, and, as a signature to post LOTE aircraft, a large air filter just forward of the engine intakes. The LOTE program effectively marked the real end of the Sea Kings’ ASW days, although the role had been in decline for some time before then.

Left. The ASW role of the SK50 continued until ’95 although it was used less and less in the final 18 months. By then there were only a few sonar sets in service and the cables were well short of 450 feet due to maintenance reconnections. The final ASW training sortie against a submarine was by Shark 05 (HMAS Success Flight) in Mid 1995 off the coast of Japan. It was up against a Japanese submarine that refused to go below periscope depth, so it didn’t need a sonar to find it – very dull event!

The demise of the Sea King ASW role was primarily due to the transition of that capability to the S70B Seahawks. The Sea King’s ability to deploy weapons (torpedoes and depth charges) was retained but was never used and the launch modules were eventually disconnected and ultimately removed some years later. Once the ASW capability was discontinued, Sea Kings only flew Utility, SAR, Maritime support and Defence Assistance to the Civil Community (DACC). What’s often forgotten was that at the same time it also ceased conducting DHWRS (Diverless Helicopter Weapons Recovery System) sorties using the big aluminium Shuttle cock (small image above right…click to enlarge.)

Below. 1995 Also saw the loss of the RAN’s sixth Sea King, when it crashed into heavily wooded terrain at Bamaga on 30 July. It was deployed at Weipa (in Far North Queensland) by HMAS Tobruk for Exercise Kangaroo ’95. The Sea King was dispatched to pick up a sailor from HMAS Shoalwater, but the pilots became disoriented and the aircraft settled into the trees at Bamaga airstrip, close to the tip of Cape Horn. Remarkably, there were no life-threatening injuries. A copy of the Board of Inquiry report can be seen here.

Above and Right. Operation WARDEN in September of 1999 was one of the RAN’s biggest interdiction exercises when troops were sent to East Timor to help stabilise the violence there, following that country’s vote for independence from Indonesia. HMAS Tobruk, with her 817 Squadron Sea Kings, was central to the operation.

The year saw the close of the second decade of the RAN Sea King’s life: a busy time, to be sure. But it was nothing compared to the decade ahead, when the availability of additional decks (Success, Manoora and Kanimbla), a rush of humanitarian needs and the RAN’s long term involvement in the Middle East demanded, at long last, the integration of fully autonomous Ships’ Flights far from home and for very extended periods.

It marked a new chapter in our small Fleet Air Arm, which, with the help of the indomitable Sea King, rose to the task with distinction.