1962 was a momentous year for me. It was the year I first fell in love and the year I joined the Royal Australian Navy. There may seem no direct connection between these two events but they followed along, quite naturally, as a story of… ‘Boy meets girl… They fall in love… Girl runs off with someone else… Boy joins the French Foreign Legion!’ In this case the French Foreign Legion was replaced by the Royal Australian Navy which seemed to be the only service recruiting at the precise moment I needed a sanctuary.

1962 was a momentous year for me. It was the year I first fell in love and the year I joined the Royal Australian Navy. There may seem no direct connection between these two events but they followed along, quite naturally, as a story of… ‘Boy meets girl… They fall in love… Girl runs off with someone else… Boy joins the French Foreign Legion!’ In this case the French Foreign Legion was replaced by the Royal Australian Navy which seemed to be the only service recruiting at the precise moment I needed a sanctuary.

I must have been a very naive young man back then. I can recall, during the Recruitment Board interview, being asked if I would be prepared to train as Observer if I failed the Pilot Course. I happily accepted, having a vague idea that an ‘Observer’ must be someone who does lookout duty from a crows nest or some such. Fortunately no one on the Board thought to ask what I thought the ‘Observer’ duties were. (My excuse is that I came from the ‘bush’ and had no experience of the sea, except that I had read Treasure Island.)

As Fate would have it the career I stumbled onto was a short service commission as a naval aviator to train on Winjeels – fixed-wing aircraft based on the British Piston Provost – with the RAAF at Point Cook, Victoria, and then Bristol Sycamore helicopters at 723 Squadron, at Nowra, NSW. This concurrence determined that I had the very dubious distinction of being the last student to graduate from the Sycamore basic flying course that commenced around October 1963, and, a very lonely course it was as my only student companion dropped out fairly early on in training.

The following course had to await the introduction of the UH-1B Bell Iroquois to 723 Squadron. About half of my first couple of weeks training were spent with a succession of staff pilots, LCDR David Orr, LCDR Ken Douglas, and Lieutenants Al Riley and Brian Courtier, and a succession of weird tasks focussed on ‘torpedo dropping trials’ in Jervis Bay. I vaguely recall that this was part of the Ikara trials developing torpedo attack procedures. I spent more time as a spotter for yellow dye patches and lost torpedoes than actually flying.

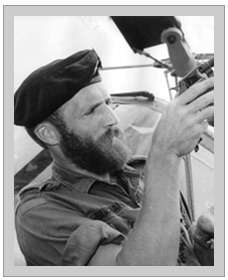

This photo of the cockpit of the only known still-flying Sycamore in the world (belonging to the Red Bulls) gives a good idea of the control layout: with individual cyclic sticks for each pilot, but only one shared collective lever with its peculiar right-angle twist grip throttle. (Red Bulls). A video of the Red Bulls sycamore doing an air display in 2018 can be seen here: well worth watching as it demonstrates the agility of the aircraft.

By the time Lt Tony ‘General’ Booth, RN took over my formal flying training I had experienced several different prototypes of the Sycamore, including, I swear, a prototype that had only one collective lever (for power and rotor blade pitch control). This lever also had a throttle attached at right angles to the lever, something like a very short motorcycle throttle. Both pilot positions had its own attitude control (‘Joystick’) but the pilot had to be a bit ambidextrous because if he had the left seat he had to control attitude with his left hand on his joystick while he controlled power and rotor blade pitch with his right hand on the centrally located collective lever. If he was in the right hand seat he used his right hand on his joystick, for attitude control, and left hand on the collective lever for power and pitch control. This lever, if you are still paying attention, you will remember was located in the centre of the aircraft for joint use by either pilot. (It was not easy to write this paragraph let alone fly the beastie).

I must confess that, generally speaking, I found flying the Sycamore to be a constant battle, not as much against gravity, or turbulent air, or rain, or cloud, or any of a pilot’s natural enemies, but, rather, against the Sycamore itself. For a start, when you got it up to a hover it hung in the air askew with one main wheel (I think the left) far lower than the other side. This meant that as you pulled up to a hover, the sensation was that you were rolling over. Now, there was a very good reason for this peculiar attitude. It was so that the aircraft could fly reasonably level at cruise speed, around seventy knots (130 kph). This peculiarity was the result of the helicopter‘s geometry in flight which resulted in the tail rotor being quite a bit higher than the main rotor.

This circumstance caused the aircraft to roll towards one side or the other whenever the rudders were used, i.e. constantly. Even more alarming was the Sycamore‘s susceptibility to “Ground Resonance”. This harmless sounding state can still make what few hairs I have on the back of my neck raise up at the memories.

Ground Resonance is a situation that helicopters with ‘drag hinges’ are prone to. Drag hinges help control the position of individual rotor blades in their rotational plane as they provide the aircraft’s lift. The drag hinge ensures, when it works properly, that a couple of rotor blades don‘t bunch up together as they travel around the pilot’s head. If two blades ‘bunch up’ this causes a very uncomfortable ride, somewhat akin the effect that tying an anvil to the tip of one rotor blade would have. For the Sycamore the effect was accentuated by the helicopter having a hydraulically damped three wheel (two main wheels and nose-wheel) undercarriage. If ground resonance occurred on touchdown the pilot had to correct the situation immediately to avoid disintegration of the helicopter. It sounds an unlikely story doesn’t it? But, when I started my training at 723 Squadron my compatriots were only too happy to point out bits of a wooden rotor blade sticking through the hangar wall. These, they said, were from an incident a couple of months earlier, adding that the destroyed aircraft had broken up in about twenty seconds. It also seemed to me that, the more delicately the aircraft was handled during the most critical periods, the more likely you were to encounter ground resonance. My excuse for ‘firm’ landings.

There was another peculiarity the Sycamore enjoyed which related to its fuel system. Basically, the longer you flew, (and the more fuel you used) the lower the nose angle would become until you reached the stage where you would not be able to get the nose high enough to physically hover the aircraft. This situation resulted, I vaguely remember, from the location of the main fuel tank being placed so far aft of the main rotor hub. The pilot had to control this attitude change by pumping anti-icing fluid into a special tank in the tail of the aircraft to counter the fuel weight loss. You performed this manoeuvre by the periodic use of a hand-pump to force the anti-icing fluid back to tail area tank. To perform this essential task it was quite useful to be able to use one knee to help hold the collective lever up in place as its friction brake could not be relied on, and you certainly did not want to take your right hand off the joystick unnecessarily.

Of course the Sycamore had no automatic stabilisation, nor rotor speed control, very little excess power – during winching training, on hot summer days, often you would find yourself winching the aircraft down rather than winching someone up – and it was essential to remember to put a large lead weight under the co-pilot’s seat if there was no one actually sitting in it and etc. etc. Ohhh! And let‘s not forget the awful crystal-based VVHF radio sets, a limit of about 7 channels. Better yet. Let‘s forget about them.

All-in-all, I tend to remember my Sycamore flying more from frequent trauma than pleasure. Mind you, once I had completed my initial training, and waited for a place on the next Wessex helicopter AFTS (Advanced Flying Training Course), I did have fun doing unlikely things like: spraying the married quarters and other living areas for flies from a Sycamore equipped with spray booms; and as I lived on base I was usually the only pilot available for the dawn flight to clear the airfield of kangaroos, to allow the airfield to open and commence normal flying.

As I neared the night flying segment of my course I was introduced to the harsh reality of the operational risks and dangers of service life generally. Near midnight on February 10, 1964, I was called down to 723 Squadron to join Lt Booth and a crewman, I think ‘Pancho’ Walter, as extra eyes in a search for survivors from the HMAS MELBOURNE/HMAS VOYAGER collision. When we flew to the collision area and set up a search pattern, all we encountered was the incredible spread of debris. It may not seem like a difficult task but, as the Sycamore was not equipped with much in the way of instrumentation it was very difficult to guess our height above water with a searchlight: the barometric altimeter indication was very imprecise. Moreover, heading control, to plan a square search pattern, relied on the accuracy of an E2B oil bath compass that had more movement than a belly dancer. I vaguely recall, next morning, we had another couple of hours searching.

I guess, as I scan what I have written, the overall impression I’ve given of the Sycamore helicopter is very negative. I must correct this by pointing out that my training on the Sycamore helped me to become a far better pilot than I probably would have been I if did not have to work so hard to cope with its vagaries. By an extraordinary, albeit tragic coincidence, on 3 June 1969, I was serving a punishment posting as Mirror Control Officer on HMAS MELBOURNE when it collided with USS FRANK E. EVANS. My posting was due to an unauthorised low-flying incident in a Wessex aircraft about eight months earlier. I recall my relief at how easy I found it to fly the Wessex after such an absence and credit my experience with the Sycamore many years earlier for the adaptability. The following year it also gave me the confidence to land a UH-1H helicopter on the deck of a damaged patrol boat on a river in the U-Minh forest of South Vietnam. But that‘s a story for another time.

My final flying posting was back to 723 Squadron, this time as CO but, even better, to fly Hueys and the Bell 206.

Jim Buchanan’s DFC:

“LEUT J. C. Buchanan, RAN Helicopter Flight Vietnam, fourth contingent, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for conspicuous gallantry. On 4 December 1970 Buchanan performed an extraordinary act of flying skill whilst operating in the U Minh Forest area. The RANHFV, which at this time was based at Dong Tam in the Mekong Delta region, was called to evacuate a crewman of a South Vietnamese patrol boat. When the two patrol boats were located the evacuation began, while the second boat stood off.

Lt Buchanan began the extraction of the crewman. Suddenly the group came under a heavy enemy attack. the patrol boat standing 50m away took a direct hit from an enemy rocket and was blown out of the water. Realising that the boat with which he was operating was disabled and drifting towards the enemy-held shore Lt. Buchanan pressed the skids of his helicopter onto the deck of the vessel and pushed the boat to safety. All the while, his aircraft was receiving heavy automatic weapons and 82mm mortar fire. For his coolness, determination and courage under fire in the face of a determined enemy, Lt. Buchanan was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.”