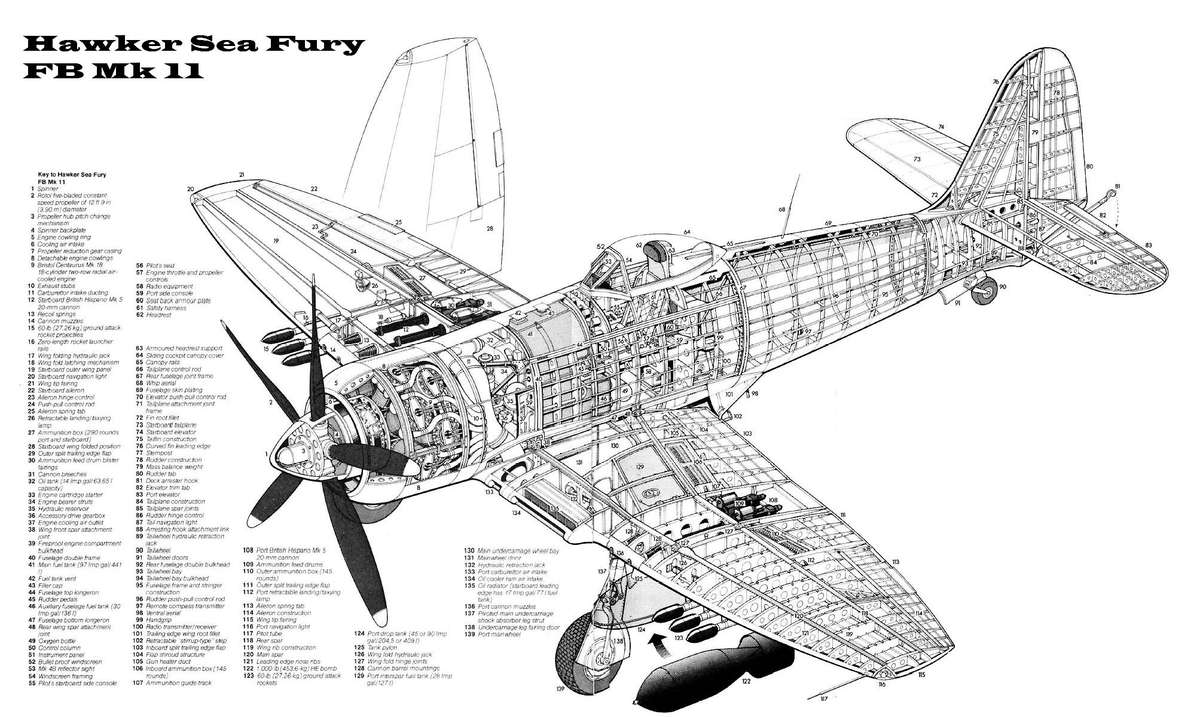

Right: A cut-away diagram of a Sea Fury, which had its origins in 1943 when the RAF saw a need for a long range fighter to counter Japanese fighters early in the Pacific campaign. A lighter and smaller version of the Tempest was suggested by Hawker’s design team, but the Admiralty’s requirement for a new interceptor saw an opportunity to combine both proposals into one airframe. As it turned out, the land based version was cancelled in 1945 with the end of WW2 in sight, but the naval career of the new fighter was assured. (Click to enlarge).

Interestingly, the first production model of the Sea Fury (with an “F.X.” nomenclature) was designated as a Fighter only. It only remained in RN front line service for a short time before being replaced by the FB (for “Fighter-Bomber”) Mk. 11. This change was driven by the RN, who saw a need for an aircraft with ground-strike capability, and which believed the fighter version to be capable of such a role. The FB.11 variant differed insofar as underwing hardpoints were fitted, to enable the carriage of ordnance such as bombs and rockets. The hard points also allowed external fuel tanks to be fitted, giving a total range of some 1,140 miles (1,673km). The FB.11 also had provision for Rocket Assisted Take Off Gear (see photo later in this collection with an explanation), and its maximum all-up weight was increased to 14,650lb. The RAN only ever operated FB.11s.

Below: HMAS Sydney arrives at Jervis Bay in preparation to unload her precious cargo on May 25th 1949. ‘Operation Decanter’ commenced at 0800 when the group officer went ashore. During the day three F.I.R. aircraft were disembarked and towed successfully to Jervis Bay airstrip (the Fireflies were taken by low loader). Nine aircraft were disembarked to JB the following day, and some F.A.E. aircraft taken to RANAS Nowra. The operation was complete by 1500 on Friday 27th May. All JB Sea Fury aircraft were gradually towed to Nowra, typically in convoys of eight aircraft, with the last being delivered on Sunday 29th. In fact, the road to JB had been widened and sealed to allow the evolution to occur.

The 805 Squadron diary reports that the Squadron offices were still under construction, with painters, electricians and telephone linesmen still working, and that the runways of the air station were ‘in no state whatsoever for a full flying programme at the moment’, although there was no reason given.

There were other problems too: only 100 gallons of Sea Fury engine oil was to be found at the air station, which held up the process of de-inhibiting the embalmed aircraft. There was only one fuel bowser, too, with a limited capacity of only 600 gallons, and every time it needed to be filled it had to drive into Nowra town some 6.5 miles away. One Squadron estimated it would take about 12 hours to refuel all its aircraft, should that be required.

Despite these setbacks the first Sea Fury flew took off from RNAS Nowra at 1000 on Friday June 10th, as the runway was at last finished (or at least enough for flying). This marked the beginning of flying operations at the Naval Air Station, and the Fleet Air Arm had its footprint on Australian soil for the first time.

Above. The initial batch of 25 Sea Furies were brought to Australia aboard HMAS Sydney as the fighter component of the 20th Carrier Air Group. A second batch of 32 aircraft arrived in November 1950 (again on HMAS Sydney), two were delivered by ships “SS Sussex” and “SS Stentor” later in March and May 1950 respectively, and further small batches arrived via Sydney and Vengeance between 1952 and 1954. A total of 93 aircraft were thus delivered and another 8 were received from the Royal Navy in Korea in 1951 to bring the total number of 101. The images above show Sea Furies being delivered to HMAS Albatross after their long journey from the UK. The arrival of the first aircraft must have been a momentous event as they marked the beginning of an operational Fleet Air Arm in Australia, as well as delivering a potent force projection. The Sea Furies had a relatively small service life and each aircraft was to suffer its own fate: Sea Fury VW626, shown above right being towed though the main gate of HMAS Albatross, survived its flying days but suffered the ignominy of the scrapyard in June of 1957.

Below. Another shot of a Sea Fury being delivered: the terrain suggests it is traversing the eastern side of Nowra Hill, not far from the main gate of HMAS Albatross. The antiquity of the lorry towing the aircraft gives a real sense of the era, now nearly seventy years ago. (RAN images)

Left: This photograph, found in the Fleet Air Arm Museum in 2018, simply has ‘Sea Furies in reserve at NAS Nowra’ inscribed on the back. Like every picture, it tells a thousand words. The second batch of Furies, including the specific aircraft in the foreground, were received at RNAS Anthorn (the RN Aircraft Receipt and Dispatch Unit) on 14July1950 where they were embalmed (on 18Aug50) ready for their journey to Australia. VX756 was then embarked aboard HMAS Sydney at King George V Docks in Glasgow shortly thereafter, and reached Australia on 07Dec50 for towing to HMAS Albatross.

It would appear it was then held in Reserve, together with other aircraft. It was then assigned to 850 Squadron as 164/K. This Squadron was short lived: it commissioned in January 1953 under the command of LCDR Reginald Wild RAN (who was killed in a flying accident shortly thereafter) and decommissioned less than 18 months later when Vengeance was returned to the UK. After a varied career with 805 Squadron the aircraft was Struck Off Charge (SOC) in Oct 1965 after being used for fire fighting training at the fire ground. (RAN image).

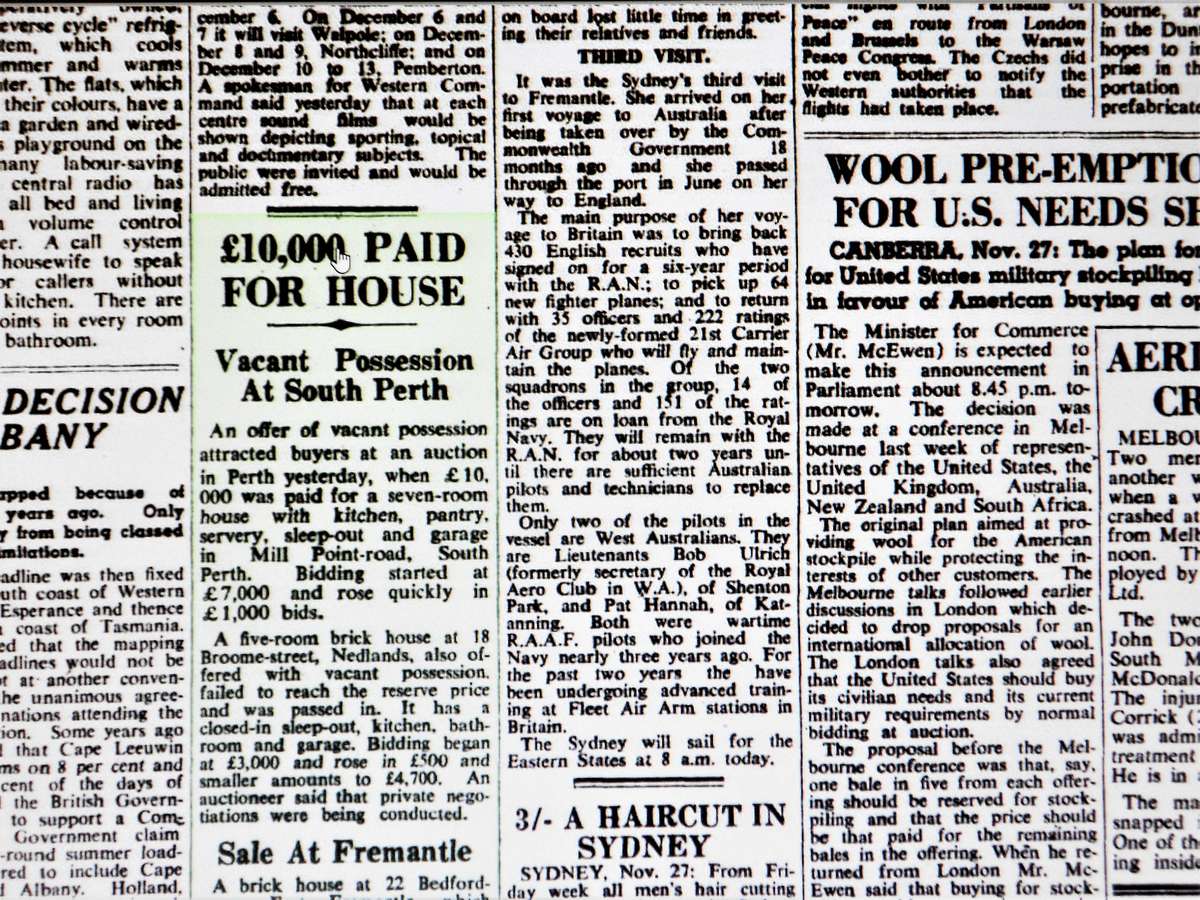

Above (three images): Sydney’s second delivery of aircraft brought the 21st CAG home, together with 23 Fireflies, 32 Sea Furies and about 100 tons of air stores. The three clippings tell something of the story from left to right: [1] Copy of the 17Oct50 page from HMAS Sydney’s Record of Proceedings [2]‘The West Australian’ 28Nov50 reports on the arrival of Sydney at Fremantle (Trove), and [3] ‘The Age’, 05Dec50 reports on the brief visit to port Melbourne (Trove). The ship then sailed to Jervis Bay to unload both the aircraft and the CAG. Unless you have bionic vision you may want to click on the images to better read them.

Left: Sea Fury aircrew making their way across Sydney’s Flight deck for the camera in Hobart in 1951. From left to right: CO LCDR Jim Bowles, SBLT Fred Lane, SBLT Ian Macdonald and LCDR Fred Sherbourne. Bowles, Lane and Macdonald were to go on to serve in Korea. This image was extracted from the excellent .pdf archive of Phil Thompson.

Below: A group of Sea Furies lined up at NAS Nowra. The UN stripes on the wings denote they were engaged in the Korean conflict, or about to be. The design was to be the last of the big propeller driven fighters, as jet propelled aircraft were already in the sky: but their high price tag was a deterrent to countries with fledgling Naval Air Arms, such as Australia and Canada, and the Sea Fury was only overshadowed by them marginally in terms of speed and altitude. Andrew Powell, who flew the Fury in Korea, has some interesting observations about piston vs jet on his page here. (Photo Neil K.)

Below: Visitors to the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Nowra will recognise this quintessential image from the days of the Sea Fury operating to straight-deck carriers. It shows a Sea Fury on short finals to the deck of HMAS Sydney on a perfect flying day, with hook down for an arrested landing. It also captures the relationship between the pilot and the Landing Signals Officer (‘Batsman’), who worked together to bring the aircraft safely to the deck. Image: AWM. Below. A loose stick of seven Sea Furies head south over Sydney harbour, perhaps bound for HMAS Albatross some seventy miles to the south. Note the warships moored off Bradley’s Head, which are most probably the heavy cruiser HMAS Shropshire and the Destroyer HMAS Quality, both of which had been decommissioned and were awaiting disposal. The identity of these ships and the lack of UN markings on the aircraft suggests the photograph was taken circa 1950 – i.e. before Korea. (RAN photo).

Below. A loose stick of seven Sea Furies head south over Sydney harbour, perhaps bound for HMAS Albatross some seventy miles to the south. Note the warships moored off Bradley’s Head, which are most probably the heavy cruiser HMAS Shropshire and the Destroyer HMAS Quality, both of which had been decommissioned and were awaiting disposal. The identity of these ships and the lack of UN markings on the aircraft suggests the photograph was taken circa 1950 – i.e. before Korea. (RAN photo).

Left: A Sea Fury taking off with Rocket Assisted Take Off Gear (RATOG). Rocket assisted take-off was used as an alternative to catapult launching for heavily loaded aircraft, or in low wind conditions. One or two rockets were fitted in jettisonable carriers each side of the fuselage, above the wing-root and angled up. The rockets were fired at a pre-calculated distance from the start of the take-off run determined according to aircraft weight, wind speed and take-off run available.

It was not without hazard. In the early ’50s an RN Firefly driver, doing RATOG practice from an airfield in Northern Ireland, pressed the firing button and the rocket motor on the port side immediately departed its carrier and neatly removed (the then) four propeller blades, plus the pilot’s beard – which spread out luxuriously from under his oxygen mask. The subsequent noise from a pilot with a burnt beard and a Griffon engine at full throttle under no-load conditions, must have been something.

RATOG was discontinued following the accident in which LEUT Barnett lost his life, when asymmetric firing caused his aircraft to spin into the sea.

Left: Sea Furies of 805 Squadron near Beecroft Range, Nowra. The image was taken in 1950 as a PR photo-shoot and shows the aircraft discharging their 3-inch rockets. It appears that Fury 116 has a ‘hang up’ rocket on the port wing – such occurrences were not uncommon and were typically due to the firing pigtail falling out in flight, although it could have been a switchology error by the pilot. (RAN image).

Below. A gorgeous shot of Sea Fury WH587 near Nowra, in NSW. It was not only a potent weapon system of the time, but regarded by many as one of the best looking prop-driven aircraft ever. This particular aircraft survived its service life and was spared the knackers yard, living on to be fully restored as a flying historic aircraft in the United States. (Image: RAN)

Left: A photograph and newspaper clipping from a Nowra local paper describe the loss of Sea Fury WV646 on 22 November 1950, when the CO LEUT Bowles experienced an engine fire whilst still about 10 miles from Nowra.

Left: A photograph and newspaper clipping from a Nowra local paper describe the loss of Sea Fury WV646 on 22 November 1950, when the CO LEUT Bowles experienced an engine fire whilst still about 10 miles from Nowra.

The 805 Squadron Diary entry for that day states that the dive bombing programme was interrupted at 1050 by the first complete engine failure in 20 CAG – quote: “…shortly [afterwards] his engine made loud noises and started to catch fire as it started to break up…in the words of the ditty – ‘black smoke came out, great flames came out, Jim Bowles came out – f*** staying in there.’ He got the speed back to 120 knots, jettisoned his hood and got out over the side with his hand around the canopy release. The tail passed over him by a clear few feet but the subsequent investigation showed that his hand must have jerked in the slipstream the necessary one inch to pull the release. It appears therefore the he lost the pilot chute and broke a few rigging lines on the aircraft as he jumped as well as burning a few holes in the canopy. His chute developed a ‘rolled periphery’ forming two lobes and his rate of descent, to his perturbation, was more than one would have wished. However, his descent took him into a 40′ tree which effectively broke the fall and a few minutes saw him on the ground having climbed down the tree none the worse for wear.”

The story goes that having extracted himself from the tree, LCDR Jimmy Bowles was in the need for a cigarette and, while he had the cigarette, he did not have a light. He therefore proceeded to the burning wreck where he was found by Gordon Hardcastle, the 20th CAG Army Liaison Officer, poking a stick into the fire to get a light. Gordon drove Jimmy back to the Air Station in the Army Jeep and, as it was 1300, went straight to the Wardroom bar where many of the Squadron had congregated to ply him with beer. As the bar shutter came down about an hour later, RADM ‘Mumbles’ Coplans appeared, unamused at the scene before him. Apparently he’d been waiting at the sick bay for the pilot to be brought in for a check. (Source:Gordon McPhee. Slipstream, April 1996). Above: a Sea Fury executes a missed approach very late on finals, to the consternation of several handlers who take evasive action. The photo dramatically illustrates the hazards of a Flight Deck, where things could turn pear shaped very quickly. (RAN image).

Above: a Sea Fury executes a missed approach very late on finals, to the consternation of several handlers who take evasive action. The photo dramatically illustrates the hazards of a Flight Deck, where things could turn pear shaped very quickly. (RAN image).

Above: This Fury is undergoing significant base level servicing, most probably in Nowra. The UN (Korea) markings indicates it was a ‘K’ aircraft (HMAS Sydney). There were five Sea Furies sequentially allocated the side number 101/K: two were destroyed in separate crashes in 1949, killing one pilot (Hare) and severely injuring another (Bolton); one was lost off Sydney in December 1950, killing the pilot (Beardsell) and a fourth crashed into Beecroft range in mid 1951, claiming the life of LEUT Leeson. One would have thought the “101” number would have been regarded as jinxed, but it continued to be used. Only the fifth aircraft – WJ279 -survived to its end of life. (Image via Jeff Chartier).

Left: A Fury on the deck of HMAS Sydney, awaiting an order to move. The lack of drop tanks and armament rails suggests it was early in the aircraft’s career. (RAN image).

Left. This photograph, supplied by Jeff Chartier, was captioned ‘HMAS Sydney Flight Trials 1949’. The take-off flap suggests a free take-off, probably during a work up, which supports the caption date. From Korea onwards, the catapult launched all aircraft. The numbers on the deck abreast each white centreline were distance to the bow for free take-offs. These numbers and the steam jet markers by the aircraft’s starboard wingtip were painted over around the time of the Korean conflict.

The Wind Over Deck Board was maintained by Flyco and set according to the planned aircraft weight and wind over deck speed. This board had room for two aircraft (Sea Fury, Firefly or “Light Sea Fury”, “Heavy Sea Fury”, etc.) slots. Flyco had a table for aircraft type, weight and planned windspeed. Sydney always had a catapult, unless it was down for maintenance.

The object in the bottom right corner of the photo looks like the Number 1 Barrier knuckle going down, just in time. (Info courtesy of Fred Lane).

Left: Sea Fury VX751 after an engine failure forced a landing at a bush strip on Cape Gloucester, New Britain on 10 September 1952. The aircraft was acting as a communications relay for Fireflies and Sea Furies in transit from HMAS Albatross to rendezvous with HMAS Sydney, which was enroute to the Monte Bello nuclear tests. The pilot survived the crash and the aircraft was subsequently stripped of useful components before being destroyed. (Photo: Jack Duperouzel).

Above Left: A group of maintenance personnel pose with their Sea Fury. The names have been lost in time, but if anyone knows please tell us! Above Right. A cut out schematic of the Sea Fury’s cockpit (Drawing: P. Cooke. Click image to enlarge). You can see a copy of the original Pilots Notes here, but be patient while it loads…its a big document.

Below: This image gives some idea of deck operations. The Sea Fury on deck has just landed – number 3 (or 4?) wire is being retracted and the flaps do not seem to be fully up, so the wings should not yet be selected to fold. A second aircraft is approaching the deck to land, with undercarriage and flaps down. He appears to have about 40° still to turn, which suggests he is low and late. In a worked up state, the second aircraft would nearly be in the finals groove at that height. (RAN photo from the Gordon Evans collection. Technical advice courtesy of Fred Lane.)

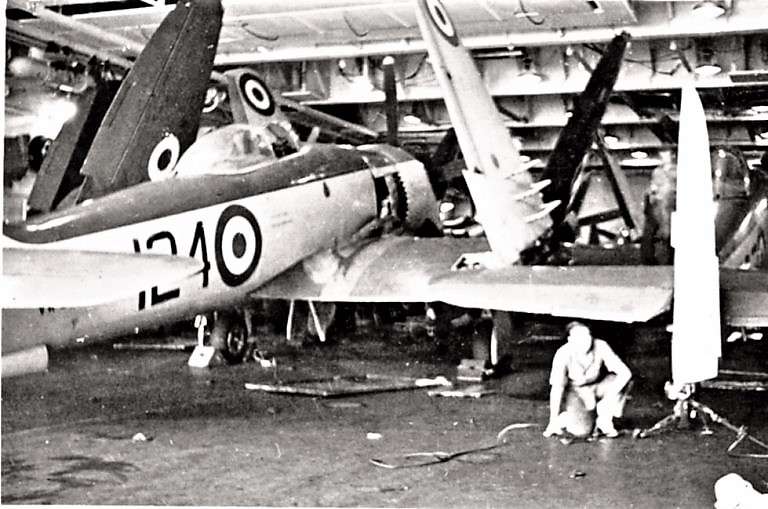

Below: Whilst photographs of flying Sea Furies are common, images showing them below decks are hard to find. The two photos above are not particularly good quality but do give an impression of the hangar deck aboard HMAS Sydney, and aircraft either stored or undertaking maintenance. (unknown source).

Above Left: A Sea Fury preparing for a free deck take off aboard HMAS Sydney. Once the Korean conflict started, free take-offs were abandoned as deck space was at a premium and aircraft were typically more heavily laden. The white numbers painted adjacent to the dotted centre-line were also removed as they were superfluous for catapult operations. Above Right: In contrast, this Fury has been catapulted. A second aircraft is lining up for dispatch and others await their turn. During operations a carrier’s flight deck has often been described as one of the most dangerous places on earth with high winds and moving aircraft and propellers a lethal combination in a small area. A/SBLT John McClinton was to find that out to his cost, when he walked into a revolving propeller in early 1954. (RAN images).

Below: One of those photographs that could almost be a painting. It shows a Sea Fury about to land on HMAS Sydney in 1953, although the exact date is not known. The LSO is signalling to the pilot and more aircraft can be seen in the distance. The RESDES is escorting to one side. The photograph is from the collection of Kevin Pavlich, who is the cine photographer in the foreground (every landing was filmed for later analysis) but the photographer’s name has been lost in time.

Above. Crew members study damaged aircraft on the deck of HMAS Sydney after Typhoon Ruth had passed. She had been lying at anchor in Sase Bo Harbour in Japan, replenishing for her next Korean War operational patrol, but the severity of the approaching storm and the restricted nature of the anchorage forced her to take to sea. She experienced the most critical phase of the typhoon from 5pm to midnight on 14 October 1952, with winds exceeding 68 knots. (RAN photo – CPO Alan White).

Above. Crew members study damaged aircraft on the deck of HMAS Sydney after Typhoon Ruth had passed. She had been lying at anchor in Sase Bo Harbour in Japan, replenishing for her next Korean War operational patrol, but the severity of the approaching storm and the restricted nature of the anchorage forced her to take to sea. She experienced the most critical phase of the typhoon from 5pm to midnight on 14 October 1952, with winds exceeding 68 knots. (RAN photo – CPO Alan White).

Below Left: A group of Sea Furies approach ‘mother’ in loose formation. Below right (1) and (2): Aircraft accidents were relatively common, given the size of the deck, the number of aircraft aboard and the rudimentary landing aids. Most involved striking the forward barrier which was raised to protect parked aircraft on the bow section of the ship. The advent of the angled flight deck, which was first introduced when HMAS Melbourne entered service, removed this particular hazard, although flying operations remained a dangerous occupation. (RAN images).

Above: Another mishap during the work up for Korea. On 18 July 1951 VW626 flown by Leut Knappstein trickled over the side of the flight deck, the aircraft hanging by a prayer. Although the 805 Squadron Diary makes light of it, this was one of several significant accidents during this period. LEUT Andrew Robertson (later RADM) is reported to have recorded:

‘I was the Gunnery Officer of HMAS Anzac, the brand new destroyer that acted as plane guard for Sydney during some of the work up. Sydney had ten major crashes (within our view) in ten days as she worked up in heavy weather off Jervis Bay. Flying eventually ceased when a [new Pilot’s] Sea Fury bounced – and went over the side where the barrel of a Bofors pinned the aircraft like a moth! The pilot went up the wing like a rat up a drainpipe and so onto the flight deck. An OA was trapped under the breech of the Bofors but escaped unharmed. The plane could neither be pushed overboard nor hoisted on the crane – so back to Jervis Bay’. (Photo: LEUT Knappstein).

Above. The immediate future does not look good for this aircraft, which has shed its starboard wheel on landing. Below: Not all mishaps were at sea. Sea Fury VW640 was one of the originals delivered by HMAS Sydney, being towed though the main gate of Albatross on 31 May 1949. It served until 1953, although it was damaged two years earlier, requiring repairs by Fairey Aviation Clyde. On 18 March 1953 it suffered an engine failure on take off from Albatross and crashed into a nearby field, severely injuring the pilot, LEUT J. Bolton. The aircraft was subsequently reduced to spares in August of that year. (RAN image).

Below and left: More spills. Operating high performance aircraft to a ‘straight deck’ carrier was inherently hazardous. Most of the accidents resulted from floating over wires, or catching a late wire to strike the forward (No 2) Barrier. Few, if any, injuries resulted from such incidents although the cost on the aircraft involved was high.

Later generation carriers had angled flight decks which avoided such problems – although the incidence of ditching was proportionally higher as mishaps where a ‘go around’ wasn’t possible usually resulted in the aircraft trickling off the flight deck into the sea.

Left: Oops! A collision between WZ642 (LEUT Leeson) and WZ652 (LEUT Litchfield) on 15 May 1955 resulted in the tail of the latter being severed. This particular accident happened at Griffith, where dust from five Sea Furies revving their engines reduced visibility. Dust notwithstanding, taxying accidents were relatively common as the visibility afforded to the pilot was severely limited by the nose of the aircraft. Ronald Leeson was to die two months later when his Sea Fury crashed into Beecroft Range (below) (Photo: FAA Museum)

Below. The 805 Squadron Line Book records the above collision with customary irreverence. (FAAM image)

Below left: September 1952. Eight Sea Furies at Manus in Papua New Guinea’s Admiralty Islands group, site of the huge WW2 American and Allied bases around Seeadler Harbour. Immediately after the war the RAN commissioned part of this complex as HMAS Seeadler, but its name was changed to HMAS Tarangau around April 1950 when it was realised that ‘Seeadler’ is the German word for Sea Eagle. Below right: A few of HMAS Sydney’s air group pose with an old RAAF base squadron sign during the same detachment. Jack Duperouzel, who took both photographs, is standing second from the left. He was a Radio Mechanic at the time.

Below: One of the few surviving Sea Furies, WH587 was first delivered in 1952 and served until it was struck off charge on 23 September 1963: a relatively short life for a military aircraft. Like most restored historic aircraft it was then owned by a succession of well-meaning collectors until it was finally returned to flying status. Its last known location was San Jose, in California. Image: Jim Jackson.

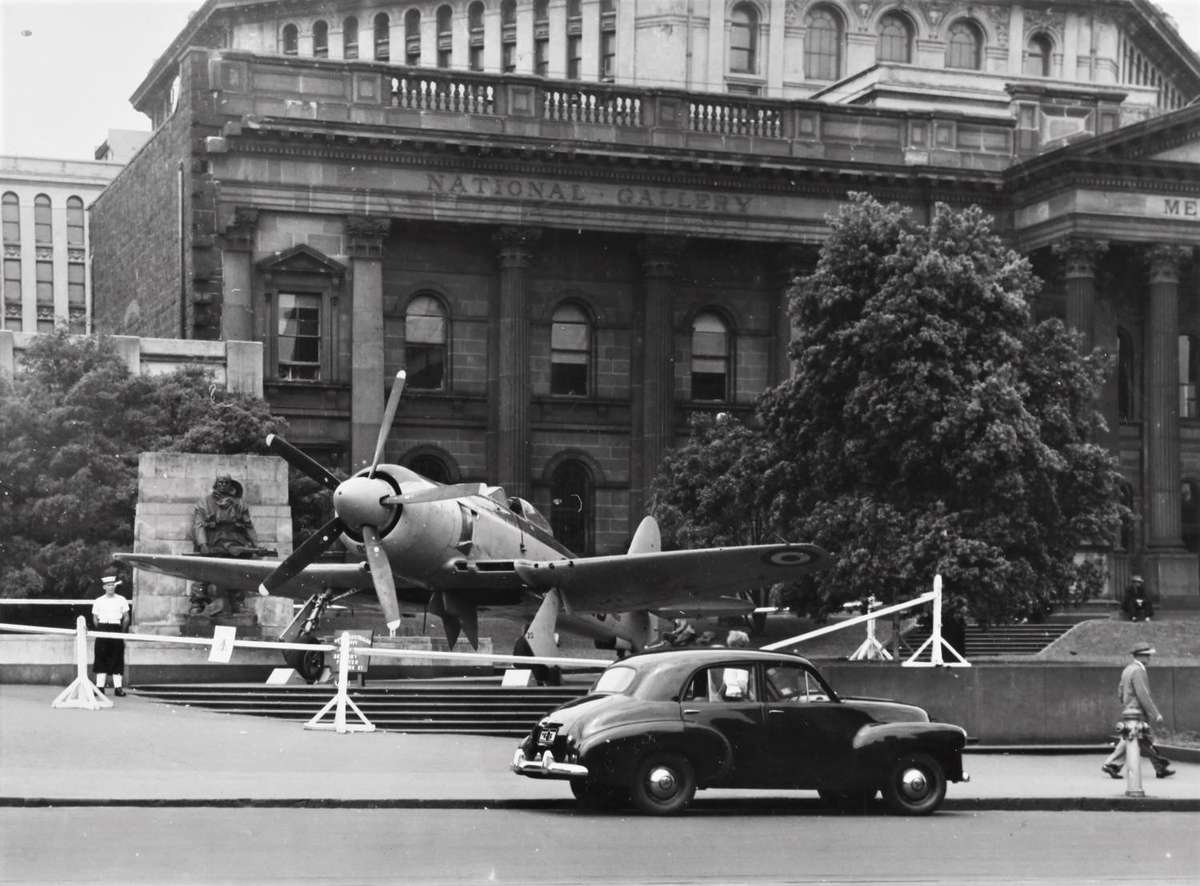

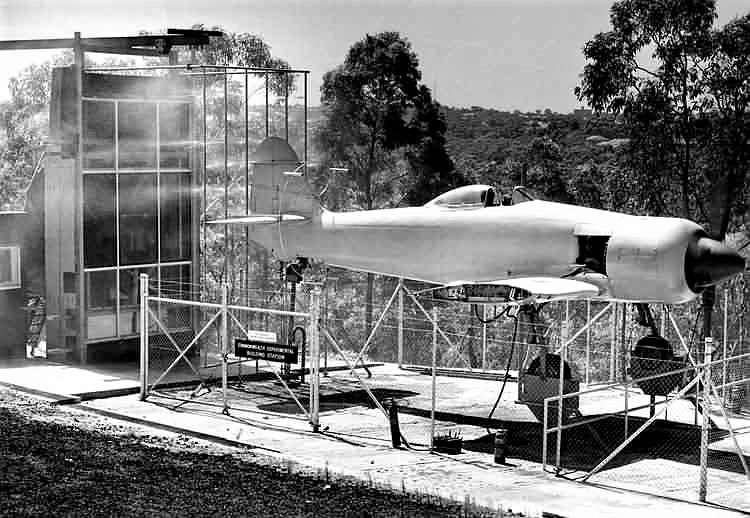

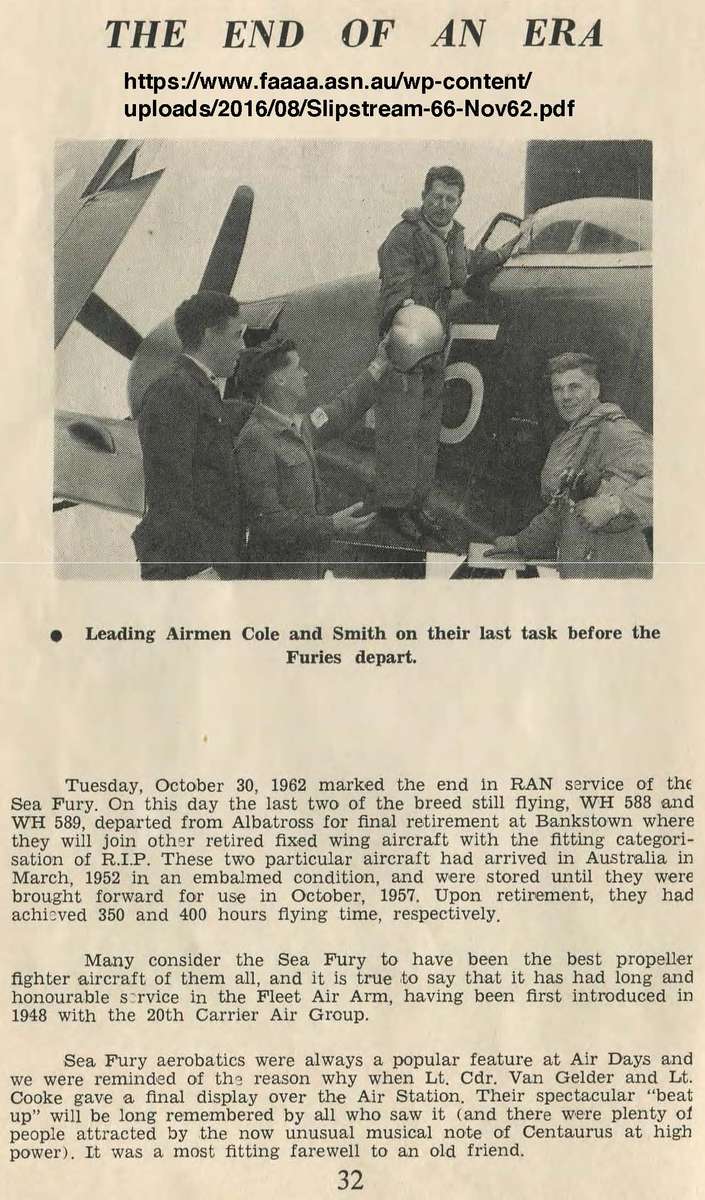

Below. A brief article in “Slipstream” magazine of March 1958 marks the final days of the few remaining aircraft. Slipstream was never magnanimous in its praise of any FAA aircraft types, so the words here were somewhat remarkable. Within a few months the last of the Sea Furies had gone, and the sound of the 18 cylinder Bristol Centaurus was replaced by the whine of the De Havilland Goblin. (FAAAA archive).

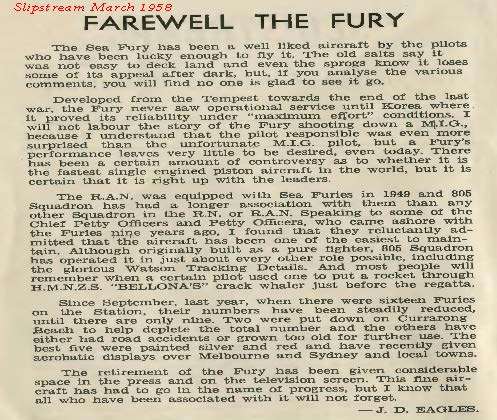

Above right. Inevitably, as the RAN’s Sea Furies reached the end of their service life they were disposed of. Most were sold to scrap merchants, but a few survived – at least for a while. VW647 was used by the CSIRO building materials testing establishment in Ryde in 1959, where it served as a wind-generator to test windows against gale force winds and rain resistance. It later found its way to a private collection in the Camden Museum of Aviation.

Right: VX730 on a low loader in 1987. According to ADF Serials, this aircaft was sold to the NSW Department of Education in 59. A Fury bearing this serial number is now on display in the Australian War Memorial, although it could contain parts from TF925 and VW232. Additional photographs of surviving Furies will be added here as they become available.