The Enigma Man

As webmaster I tend to look for material involving the RAN Fleet Air Arm, but every now and again a story emerges that is more than worthy of our interest. Here is one such story – of Lieutenant Commander David Balme ex RN Fleet Air Arm, who has died aged 95 and who led a boarding party which captured the secrets of Enigma from a German U-boat during the Battle of Convoy OB138 in May 1941, a turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Our thanks to the Daily Telegraph Obituary page, from which this article is extracted.

At midday on 09 May 1941 Commander Joe Baker-Cresswell, captain of the destroyer Bulldog, was about to order the ships of the 3rd Escort Group to leave west-bound trans-Atlantic Convoy OB318 in order to refuel at Iceland, when two merchant ships were torpedoed in quick succession. The torpedoes were fired from U-110, commanded by the U-boat ace Fritz-Julius Lemp, who failed to notice the proximity of the corvette Aubretia. Before his second salvo of torpedoes struck, Aubretia’s Lieutenant Commander Vivian Smith commenced a counter-attack with depth charges which blew U-110 to the surface.

At midday on 09 May 1941 Commander Joe Baker-Cresswell, captain of the destroyer Bulldog, was about to order the ships of the 3rd Escort Group to leave west-bound trans-Atlantic Convoy OB318 in order to refuel at Iceland, when two merchant ships were torpedoed in quick succession. The torpedoes were fired from U-110, commanded by the U-boat ace Fritz-Julius Lemp, who failed to notice the proximity of the corvette Aubretia. Before his second salvo of torpedoes struck, Aubretia’s Lieutenant Commander Vivian Smith commenced a counter-attack with depth charges which blew U-110 to the surface.

Balme on the bridge of Bulldog

Balme on the bridge of Bulldog

The destroyer Broadway attempted to ram the surfaced U-boat and all three British ships opened fire with their guns. There was panic in U-110 and the crew abandoned ship: 15 men were killed or drowned including Lemp, and 32 survivors were picked up and hurried below deck in Aubretia. The action was over in minutes, and when Baker-Cresswell stopped Bulldog alongside the U-boat he found it wallowing stern-down in the Atlantic rollers.

Balme was ordered to row across in Bulldog’s whaler to “get whatever you can out of her – documents, books, charts, and get the wireless settings, anything like that”. Jumping on to the U-boat’s outer hull he walked, revolver in hand, to the conning tower, at which point he had to holster his pistol in order to climb three ladders to the top of the tower and down again inside the U-boat to the control room. It was, he later recalled, “a very nasty moment because both my hands were occupied and I was a sitting target to anyone down below”.

The Enigma Machine

Arthur Scherbius, a German engineer, developed his ‘Enigma’ machine, capable of transcribing coded information, in the hope of interesting commercial companies in secure communications. In 1923 he set up his Chiffriermaschinen Aktiengesellschaft (Cipher Machines Corporation) in Berlin to manufacture his product. Within three years the German navy was producing its own version, followed by the army in 1928 and the air force in 1933.

Enigma allowed an operator to type in a message, then scramble it by using three to five notched wheels, or rotors, which displayed different letters of the alphabet. The receiver needed to know the exact settings of these rotors in order to reconstitute the coded text. Over the years the basic machine became more complicated as German code experts added plugs with electronic circuits.

Britain and her allies first understood the problems posed by this machine in 1931, when Hans Thilo Schmidt, a German spy, allowed his French spymasters to photograph stolen Enigma operating manuals. Initially, however, neither French nor British cryptanalysts could make headway in breaking the Enigma cipher.

It was only after they had handed over details to the Polish Cipher Bureau that progress was made. Helped by its closer links to the German engineering industry, the Poles managed to reconstruct an Enigma machine, complete with internal wiring, to read the German forces’ messages between 1933 and 1938.

With German invasion imminent in 1939, the Poles opted to share their secrets with the British, and Britain’s Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, became the centre for Allied efforts to keep up with dramatic war-induced changes in Enigma output.

Top mathematicians and general problem-solvers were recruited and a bank of early computers, known as ‘bombes’, was built to work out the Enigma’s vast number of settings.

The Germans were convinced that Enigma output could not be broken, so they used the machine for all sorts of communications on the battlefield, at sea, in the sky and, significantly, within its secret services. The British described any intelligence gained from Enigma as ‘Ultra’, and considered it top secret.

Only a select few commanders were made aware of the full significance of Ultra, and used it sparingly to prevent the Germans realising their ciphers had been broken.

A party from Bulldog prepares to board the U-boat

A party from Bulldog prepares to board the U-boat

Balme was very frightened; he expected the boat to sink, or scuttling charges to blow up at any moment, or to be overcome by chlorine from damaged batteries. The inside of the boat was dimly lit, there was a “nasty” hissing noise, and he could hear water slopping in the bilges. “I immediately went right for’d and right aft with my revolver in my hand to see if there was anybody about,” he said later. Noting that despite damage the U-boat was clean and well-kept and there was food on the table, but finding no Germans aboard, Balme called down the boarding party and “started ransacking all the treasures of the U-boat”.

In the wireless office, telegraphist Alan Long found “a funny sort of instrument, Sir, it looks like a typewriter but when you press the keys something else comes up on it”. Balme recognised this as “some sort of coding machine”, which he ordered to be unscrewed, and he organised a human chain to carry the machine and other equipment, charts and documents up the ladders and into the whaler.

Balme and Long had found an Enigma machine, the cipher device which the German U-boat service used to communicate to its fleet in, as the Germans thought, an unbreakable code. Besides that day’s settings they also recovered the daily settings until the end of June, which, when delivered later to Bletchley Park, enabled Alan Turing and his team to read the German naval “Hydra” code, the officer-only code, and, with the knowledge and experience gained, to go on to crack several other codes. Lemp’s crew were so demoralised and ill-disciplined that later in prison camp they talked freely to their interrogators about U-110 and about other boats in which they had served.

Mary Soames’s 21st birthday party at sea (photographed by Balme, who attended the occasion)

Mary Soames’s 21st birthday party at sea (photographed by Balme, who attended the occasion)

Balme and his men spent six hours inside U-110, where for some time they were left alone in the Atlantic, listening to the distant sound of depth charges while the 3rd Escort Group hunted another U-boat. When Bulldog returned, Balme passed a towline, and for a day U-110 was pulled towards Iceland, until about 11.00 on May 10 1941 when the German vessel reared its bows in the air and sank stern-first.

The loss of U-110 enabled the British to throw a cloak of secrecy over the whole affair, a cloak so dark that even when Captain Stephen Roskill, the official historian of the Royal Navy, wrote about the capture in 1959, only those already in the know were able to read between the lines and would have realised that the secret of the capture was not the U-boat but the Enigma material which was salvaged from it. Balme had been told that the truth of his secret capture would be kept forever, and was surprised when in the 1970s its secrets began to leak out.

Baker-Cresswell and Smith were awarded the DSO, Balme the DSC, and Long the DSM, for enterprise and skill in action against enemy submarines.

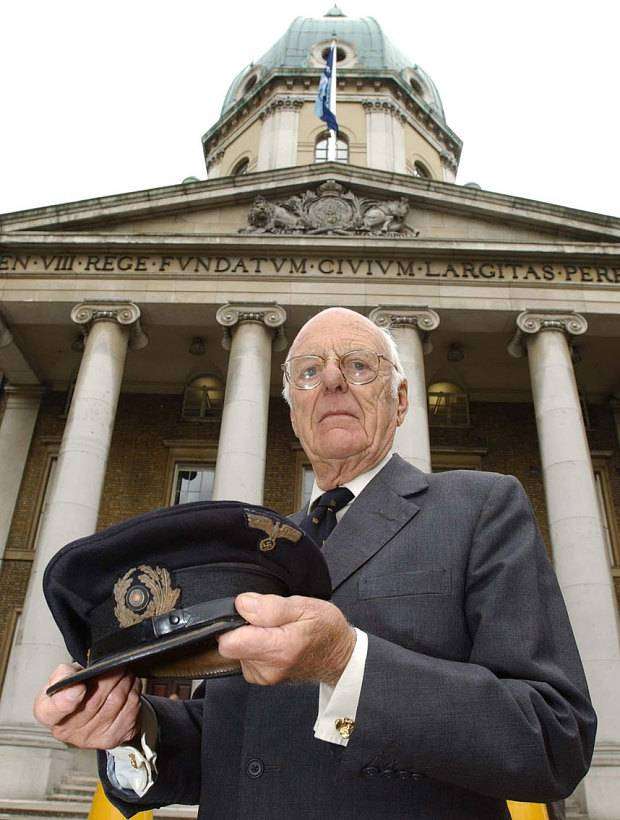

There were also breaches of security: Baker-Cresswell had told Balme to bring him back a pair of binoculars. Balme brought back two, and he used these swastika-stamped Zeiss binoculars in his yacht for 50 years. He also pinched Lemp’s cap from his cabin, keeping it as a souvenir until he presented it to the Imperial War Museum in 2003.

David Edward Balme was born in Kensington, London, on October 1 1920, of Huguenot stock. Aged 13, David entered Dartmouth Naval College in the Anson term of 1934. His naval career was unusually varied. Pre-war, as a midshipman, he served in the cruisers London and Shropshire in the Mediterranean during the Spanish Civil War; he recorded the rising tension in Europe in his midshipman’s journal. When he was re-appointed to the destroyer Ivanhoe in June 1939 she was on the Palestine Patrol, preventing illegal immigration into the Holy Land, and when she was recalled to Britain at the outbreak of war he witnessed the torpedoing of the carrier Courageous in September. In mid-October he took part in the Battle of Convoy KJF3 when two U-boats were sunk.

David Balme (right) with Terry ‘Hawkeyes’ Bulloch at the Imperial War Museum for the 60th anniversary of the Battle of the Atlantic Photo: andy butterton/pa

David Balme (right) with Terry ‘Hawkeyes’ Bulloch at the Imperial War Museum for the 60th anniversary of the Battle of the Atlantic Photo: andy butterton/pa

Balme had a very enjoyable few months on his foreshortened sub-lieutenant’s courses in Portsmouth and Greenwich in early 1940 and his next appointment was as sub-lieutenant of the gunroom in the cruiser Berwick. On November 27 1940 she fought against the Italian fleet in the Battle of Cape Spartivento, when she was hit by two 8in shells which knocked out her after turrets, killing seven men, wounding nine others and igniting a fire which took an hour to subdue.

Then on Christmas Day that year Berwick was off the Canaries escorting Convoy WS-5A when, despite being hit several times, she drove off the German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, thus saving a valuable troop convoy bound round the Cape for the Middle East. When Berwick returned to Plymouth for repairs, Balme was appointed to Bulldog as her navigator. Bulldog, he declared, was “a happy little ship and far the best time that I ever had in the Navy”. While in her he took part in several trans-Atlantic convoys, and in the occupation of Iceland.

Balme’s navigational skill led to him being selected as an observer in the Fleet Air Arm. En route to Egypt in June 1942 he commanded a party of British gunners on-board the American merchantman Chant, part of a convoy intended for the relief of Malta – but was sunk. Rescued from the water, he spent two nights in an air raid shelter in Malta before flying on to take up his duty as senior observer of 826 Naval Air Squadron.

Balme’s Fairey Albacore bombers perfected the technique of pathfinding – dropping flares for RAF Wellingtons to bomb. When he left, in February 1943, the Air Officer Commanding sent him a signal of thanks for the “magnificent work with and for the Wellingtons. There is no doubt that these night attacks were one of the decisive factors in crushing the enemy’s attack. The successful conclusion of the land battle may well prove to be a turning point in the war in Africa.” Balme was mentioned in despatches.

Next Balme qualified as fighter direction officer (FDO) and was sent to the battleship Renown, and when she brought Winston Churchill and his staff back from the Quebec Conference in September 1943 Balme studied him closely. Balme also attended the 21st birthday party of Mary Churchill (later Lady Soames). Almost Balme’s last appointment was as staff FDO in the Eastern Fleet, in the battleship Queen Elizabeth, when with acting rank he became the youngest Lieutenant Commander in the fleet. His service included a month in the escort carrier Empress directing her aircraft on photo-reconnaissance missions over Malaya.

Post-war Balme joined the family’s wool-broking business. He hunted with the New Forest Hounds and, as a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron, sailed the coasts of Western Europe. In 1999 Balme was historical adviser during the making of the Oscar-winning film U-571, which recast the capture and boarding of U-110 as an American victory. When the prime minister at the time, Tony Blair, called this an affront to British sailors, Balme, the one-time chairman of Lymington Conservatives, pointed out that it was a great film, that it would not have been financially viable without being Americanised, that the credits acknowledged the Royal Navy’s role in capturing Enigma machines and code documents, and that he was glad the story had been told in tribute to all the men involved.

Balme married Susan im Thurn in 1947. She survives him with their two sons and a daughter.

Lieutenant Commander David Balme, born October 1 1920, died January 3 2016

David Balme at the Imperial War Museum Photo: andy butterton/pa

David Balme at the Imperial War Museum Photo: andy butterton/pa