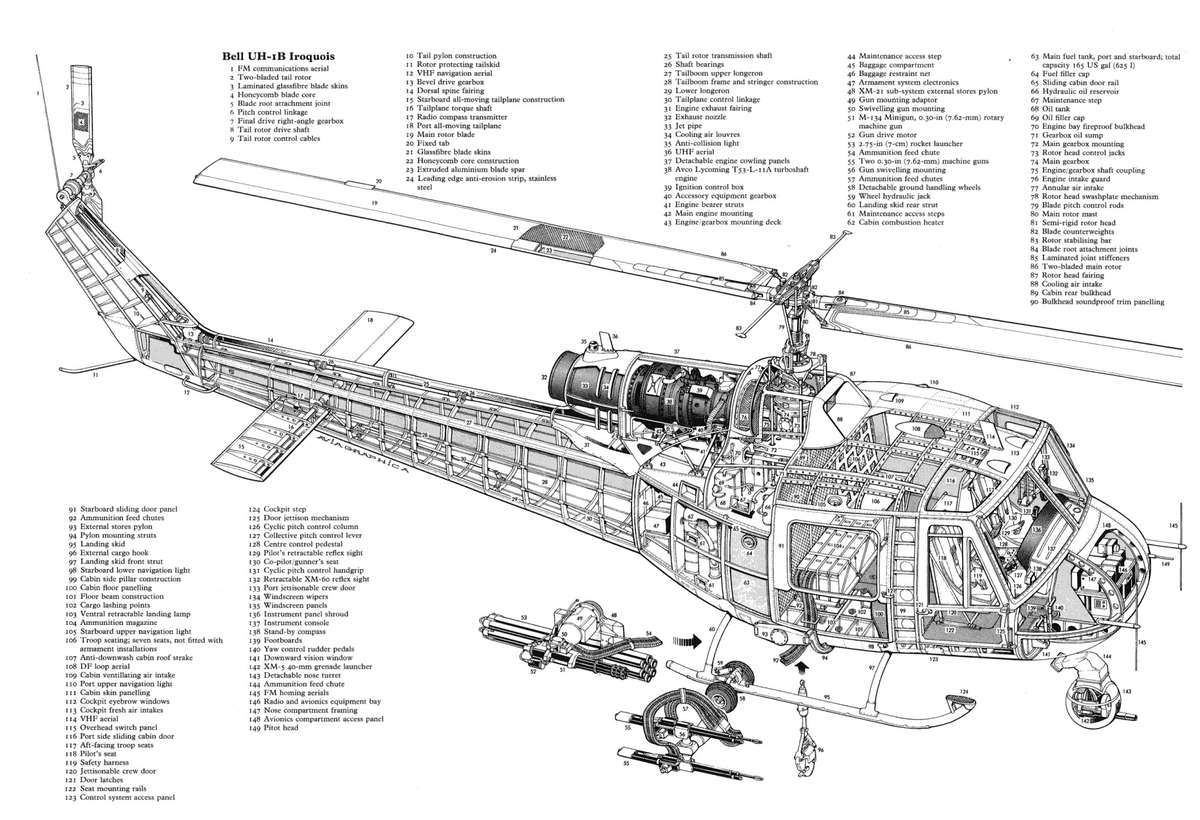

Below: By modern standards the Iroquos was of conventional design, but back in its time it was revolutionary. It was the first mass produced helicopter powered by a gas-turbine, which allowed the engine to be mounted above and behind the main rotor gearbox. This facilitated not only a simplified drive chain but also greater cabin capacity, with a good payload. The wide ‘car-style’ doors allowed easy ingress, and the simplicity of the rotor head not only saved weight but made maintenance relatively easy.

Like every aircraft acquisition, the thought and analysis started long before the shiny new toys were unpacked from the box. In the early ’60s, with rising Cold War tensions and expansion of Indonesia’s sub-surface capability, the Australian Government sought to strengthen its Anti-Submarine ability. In 1961 it placed an order for 27 Westland Wessex helicopters, which in turn generated a demand for helicopter pilots. The RAN’s ageing Bristol Sycamores were due to retire so a new trainer was urgently required, and the Bell the Bell Iroquois was selected as a suitable type. Left: Navy News of June 1964 announces the imminent arrival of the UH1-Bs.

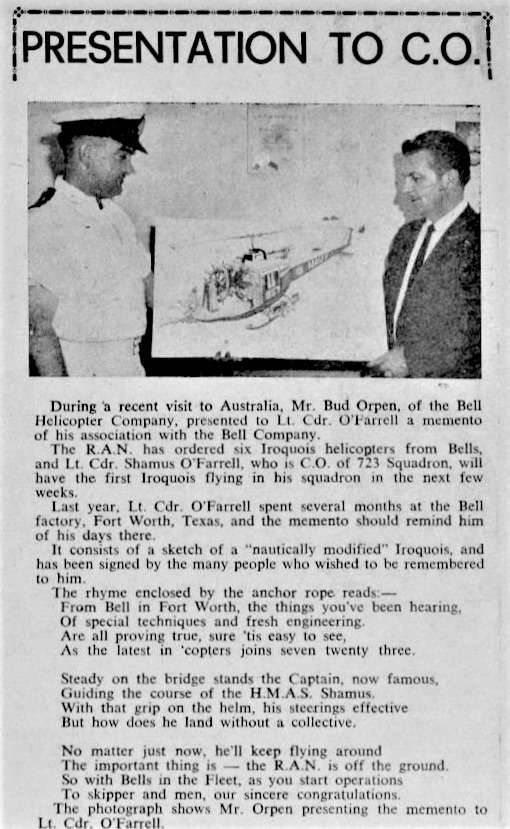

Below: Lt.Cdr. Shamus O’Farrell had been dispatched to the Bell plant in Fort Worth, Texas, to oversee the delivery of the new machines and to undertake training: he was to take command of 723 Squadron on his return to Australia. Navy News of April 1964 reports on a presentation made to him by Bell to remind him of his days there.

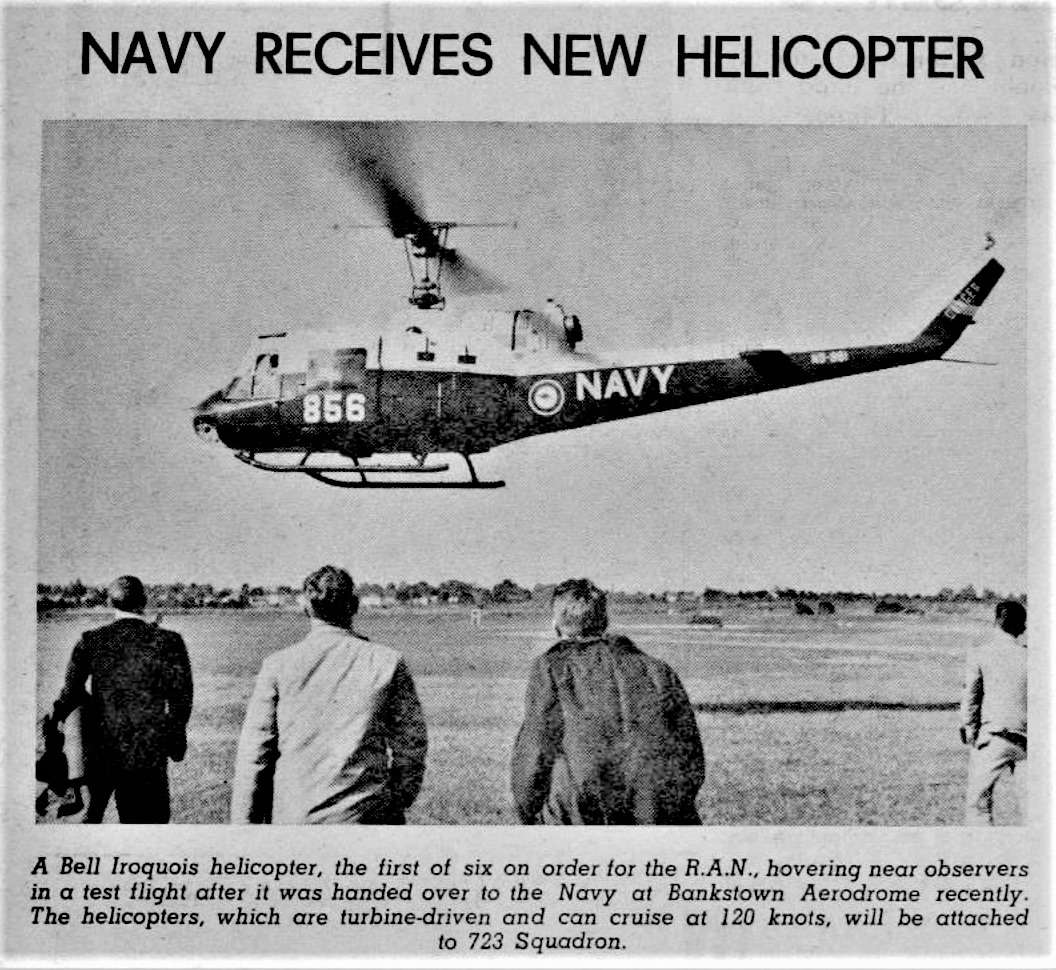

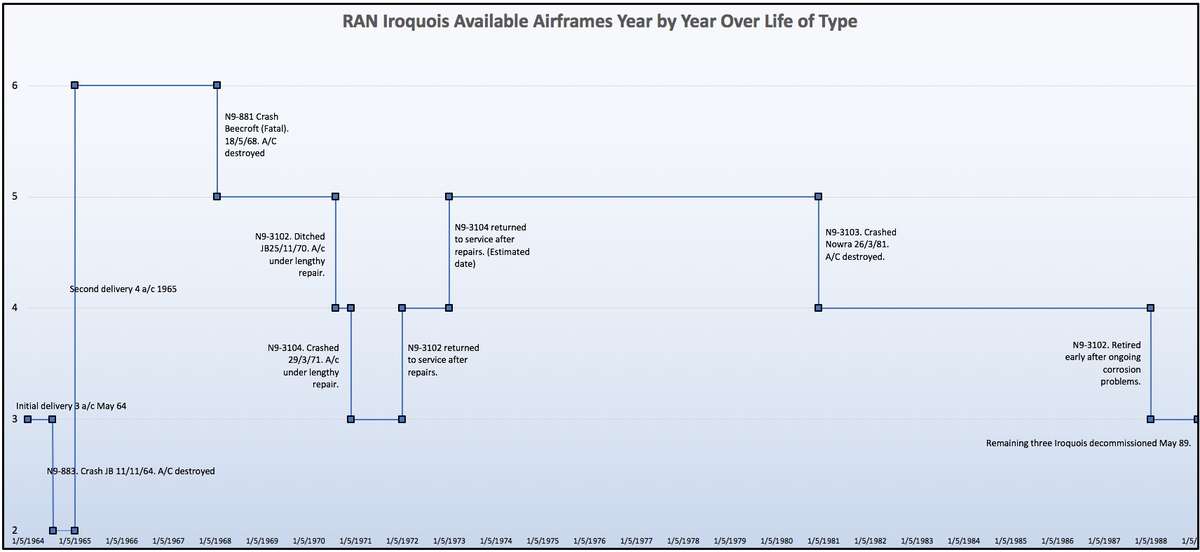

The first three RAN Iroquois were delivered in May of 1964 (N9-881-883), three more in 1965 (3101-3103) and the final one in 1966. All were delivered by merchant ships. After test flights at the Bankstown facility, they were assigned to 723 Squadron at NAS Nowra. Below: Navy News of May ’64 reports on the first batch. The Iroquois pictured was to crash six months later with the loss of three lives.

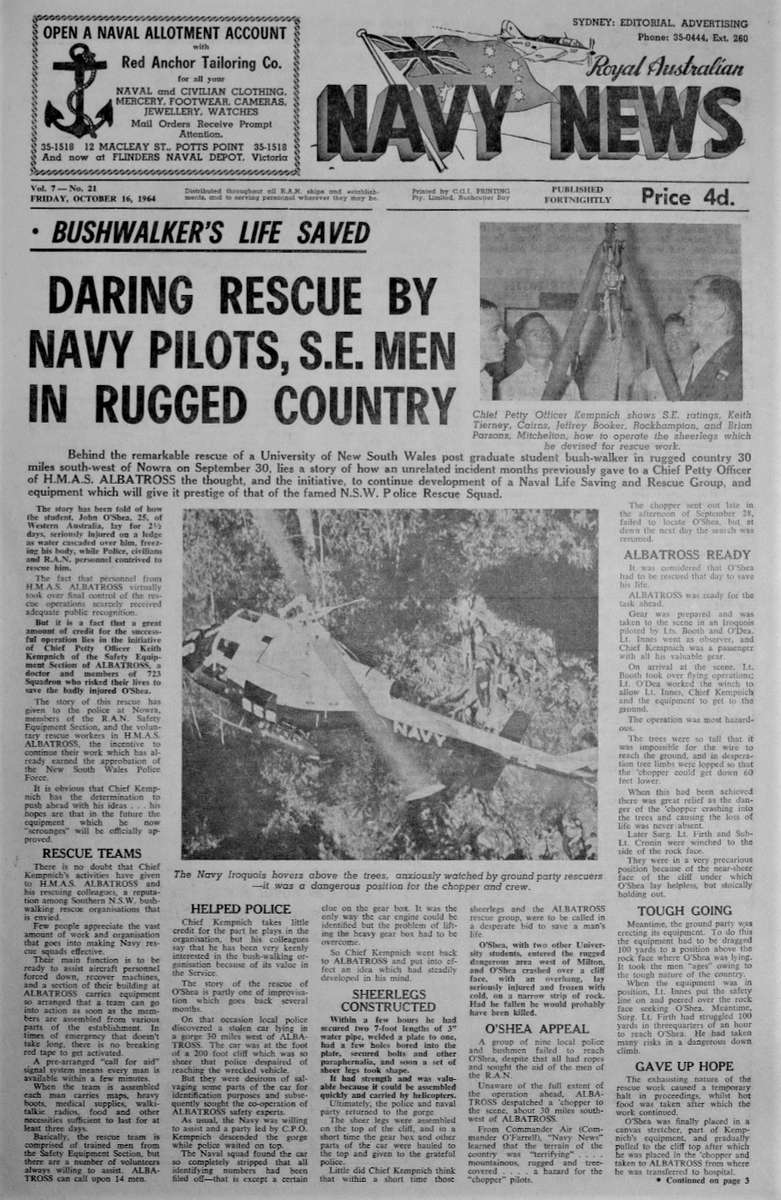

Left. It didn’t take long before the Iroquois were being used in rescues – some of which were tricky as recounted by Navy News in October 1964. It tells the story of an injured bushwalker who had been trapped for nearly three days in particularly rugged terrain not far from Albatross, and the efforts that were required to rescue him. Worth a read if you can expand the image sufficiently on your device.

Above. In a different rescue, a survivor is helped from the cabin of an Iroquois at HMAS Albatross. He was one of two plucked from the sea by 723 Squadron. The dredge, which was later declared to have been unseaworthy, struck mountainous seas off Point Perpendicular (NSW) and sank before rescuers could reach it. Two other crewmen managed to board a lifeboat and were later picked up by a passing ship. Thirteen others tragically lost their lives in the accident. A message from RADM T.K. Morrison, Flag Officer in Charge East Australia Area said: ‘SAR Operations for the dredge ALTAS were carried out in difficult and dangerous circumstances in appalling weather conditions. I am very proud the courage and devotion to duty shown and I congratulate you all on your fine efforts.”

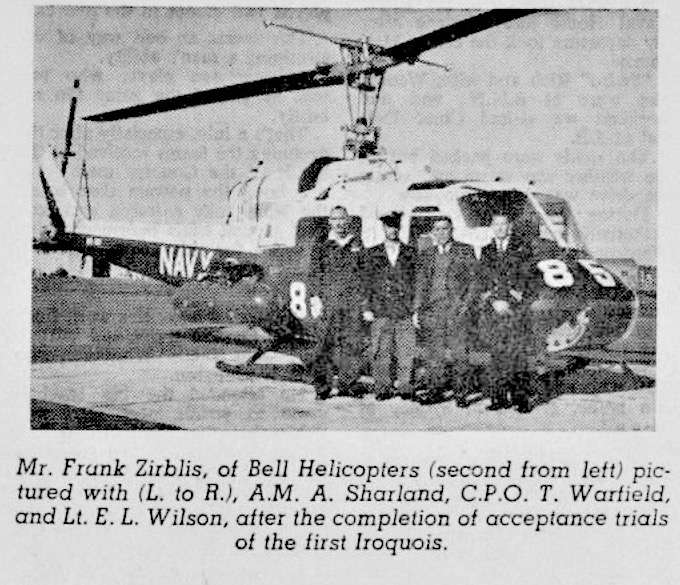

Left. This poor quality image from ‘Navy News’ of June 1964 reports on the completion of the acceptance trials of the RAN’s first Iroquois (on 5th June), which had been in the hands of De Havilland’s at Bankstown for some three months while they were modified to accept standard RAN radios (See ‘A Radio Tech’s View here). The work, which must have been extensive, was undertaken on just one aircraft as proof of concept, before starting on the remaining two in HdH’s custody. The article further mentioned that the introduction of the Iroquois will make the RAN the first Service in the world to train its helicopter pilots entirely on gas-turbine aircraft. (Click image to enlarge).

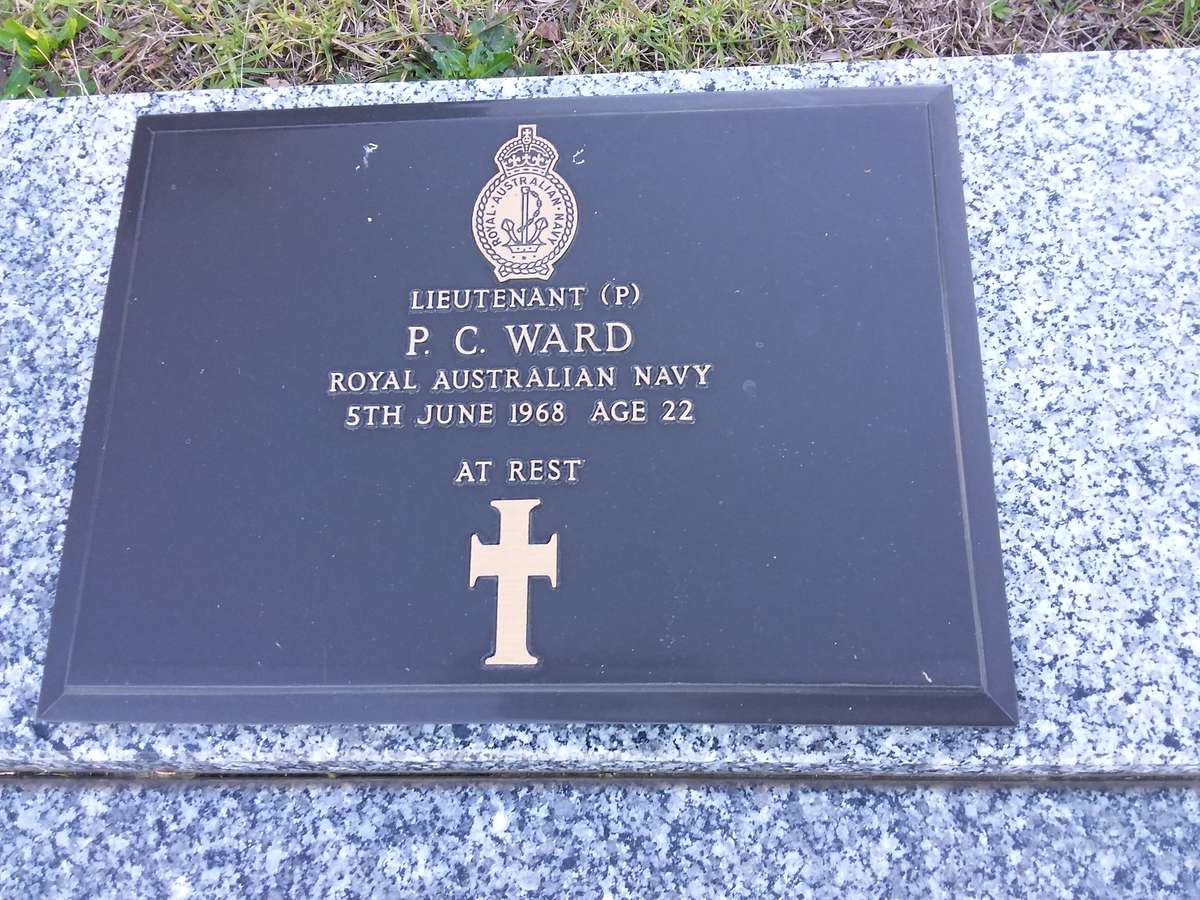

The RAN lost its first Iroquois in short order, when N9-883 crashed at Jervis Bay in Nov 64, with serious injury to the instructor (see here). Tragedy struck on 5 June 1968 when LEUT P. Ward his two crewmen were killed at Beecroft Range when their aircraft struck the ground, broke up and plunged into the sea. You can see a copy of the Board of Inquiry report here.

The RAN lost its first Iroquois in short order, when N9-883 crashed at Jervis Bay in Nov 64, with serious injury to the instructor (see here). Tragedy struck on 5 June 1968 when LEUT P. Ward his two crewmen were killed at Beecroft Range when their aircraft struck the ground, broke up and plunged into the sea. You can see a copy of the Board of Inquiry report here.

Below Left. We have no specific date for this photograph, but from the progress of the Opera House and the Charles F. Adams Class destroyer alongside would place it no earlier than March 1966. The image is useful as it not only puts the Iroquois into a uniquely Australian context, but pins the early part of its RAN life into a historical context too. Below Right: Another historical context, with this Iroquois winching a pilot near a Sea Venom. The Venoms were phased out in the closing years of the 60s. Click on the image to enlarge.

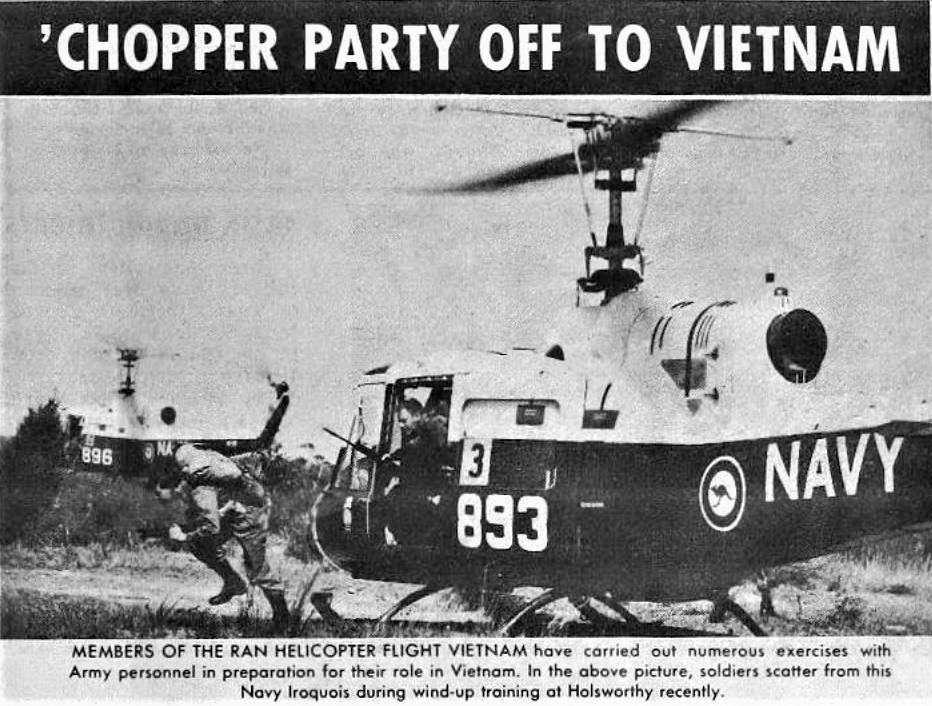

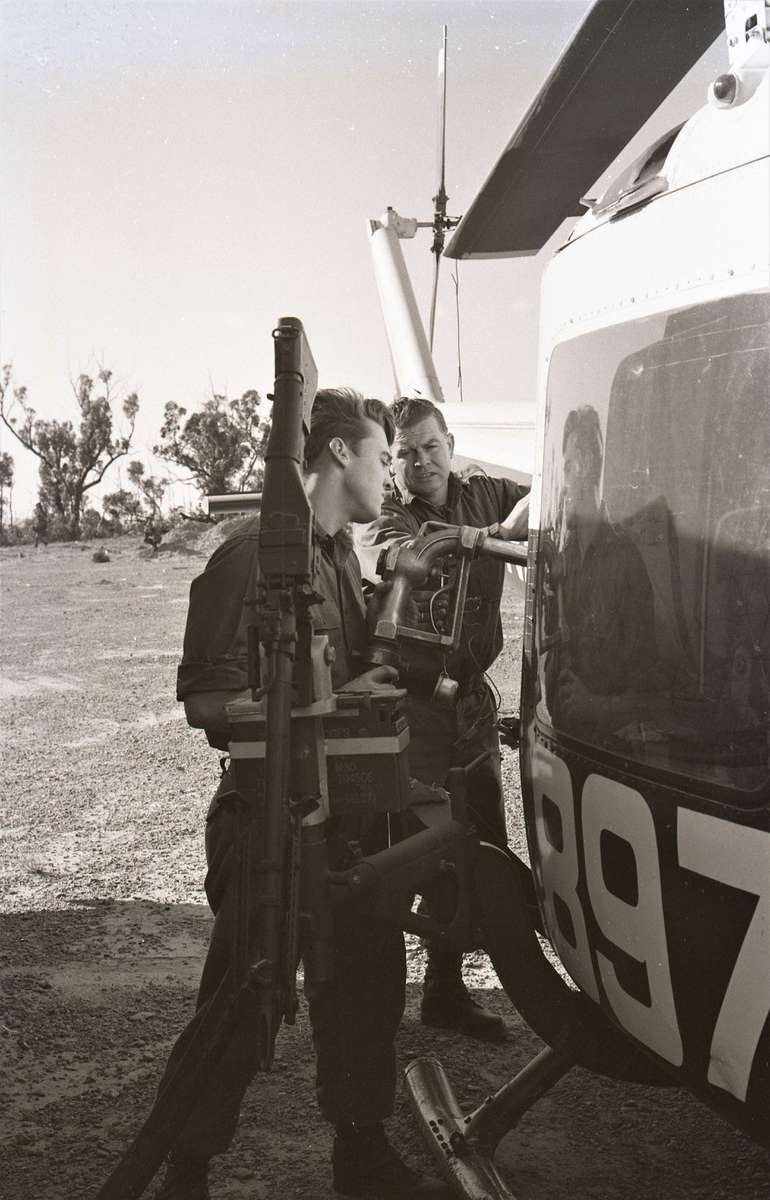

Below. Australian troops had been committed to fighting in Vietnam since ***, but no Naval air assets had been provided. A proposal for the US to provide four helicopters to be flown and maintained by Australians was rejected. But America was short of crews and their training pipeline stretched, so the suggestion that trained helicopter aircrew and maintainers be integrated into a US Army Unit was accepted, and the RAN Helicopter Flight Vietnam (HFV) was born. 723 Squadron, with its ‘B’ model Hueys, was to play a big part in training both the Flights and soldiers for the role.

RANHFV training for the first Flight commenced on 01 September 1967. The syllabus was cobbled together by reference to the Flight Operations manuals of US Army aviation battalions, but with only about six weeks available the Flight had to decide which topics to concentrate on in Australia, and which could be picked up ‘on the job’ in Vietnam. Training was greatly assisted by Major Frank Crowe, Nowra’s Carrier Borne Liaision Officer (known colloquially as ‘CBALLS’), who had competed a tour of Vietnam with the RAR.

Flying training was mainly done in the areas around Nowra but Gospers airfield (west of Richmond) was also used, particularly for joint exercises with the RAR. These inevitably brought a clash of cultures: Army ran a routine based in its operational and defensive requirements; Navy flew during the day and then prepared both aircraft and personnel for the following day, including night maintenance as required. The two routines were not easily accommodated so the Iroquois were relocated to the nearby by small town of Glen Davis.

About 60 hours of flying was achieved by each pilot. This included air combat assaults, extractions, re-supply and recce flights. Generally, the training was regarded as a good initiation of what could be expected in-country and was further enhanced over time, drawing upon the experience of returned Flights.

Right: Other detachments were to follow in later years, and although they did not employ 723 Squadron aircraft, they did use RAN FAA aircrew.

One such event was the Second UN Emergency Force (UNEF II) in the Sinai Peninsula in 1977. The mandate of UNEF II was to supervise the ceasefire between Egyptian and israeli forces following the Yom Kippur War of 1974/5. (Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial). For more about this task, see the Sidebar “UNEF II” here.

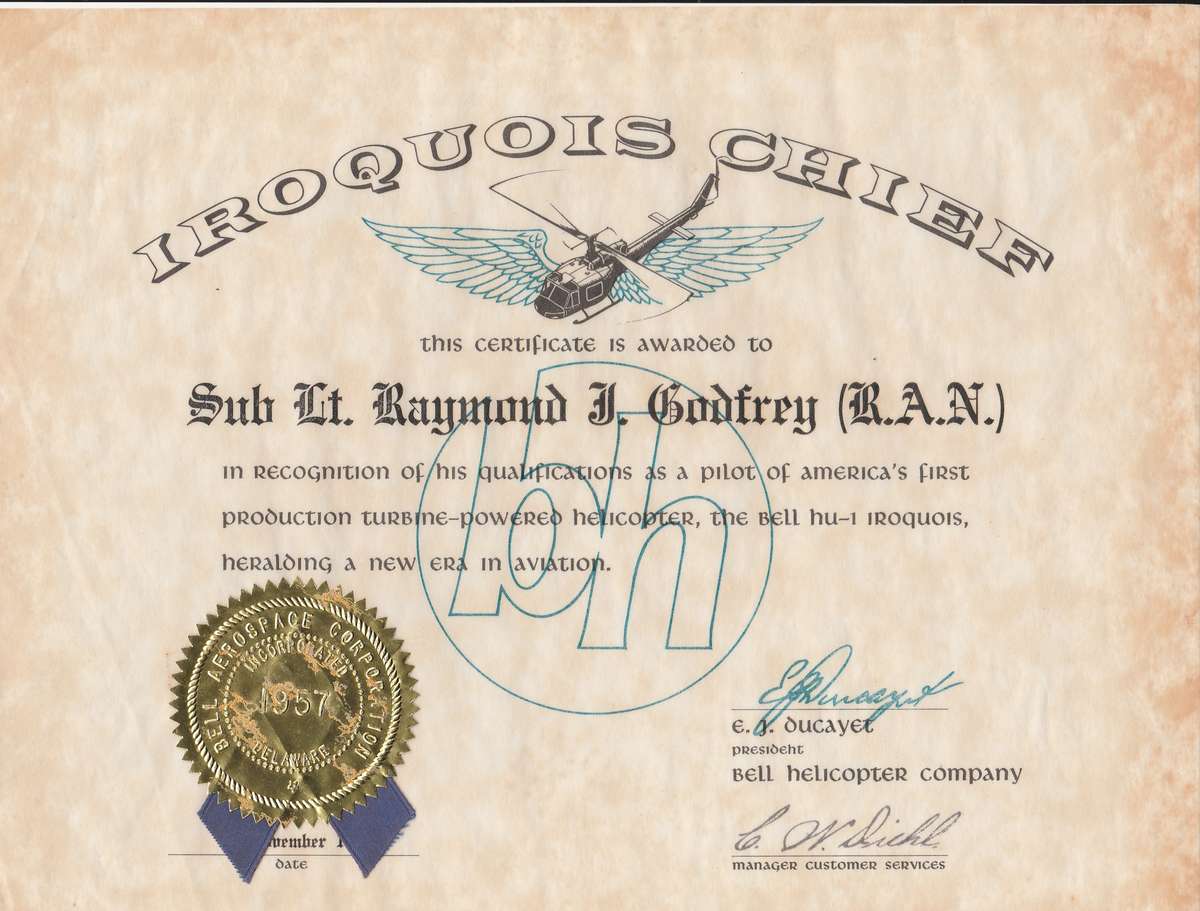

Below left: One of the early UH1B conversion courses for personnel destined for Vietnam. From left to right: LEUT Staf Lowe, SBLT Ray Godfrey, SBLT Jeff Dalgleish and SBLT Tony Casadio. All four were to serve on the first RANHFV detachment, where Casadio was to lose his life on 21 August 1968 (see Roll of Honour entry here). Below right: This Certificate was awarded to Graduates at the end of the Huey conversion by the Bell Aircraft Corporation. ‘Iroquois Chief’ is a pun referring to the leader of the native American tribe after which the aircraft was named, rather than ‘Chief’ in naval terms, or as a crew title (ie ‘Crew Chief’). It is not known how long such certificates were handed out, but we suspect it was only for the first few courses.

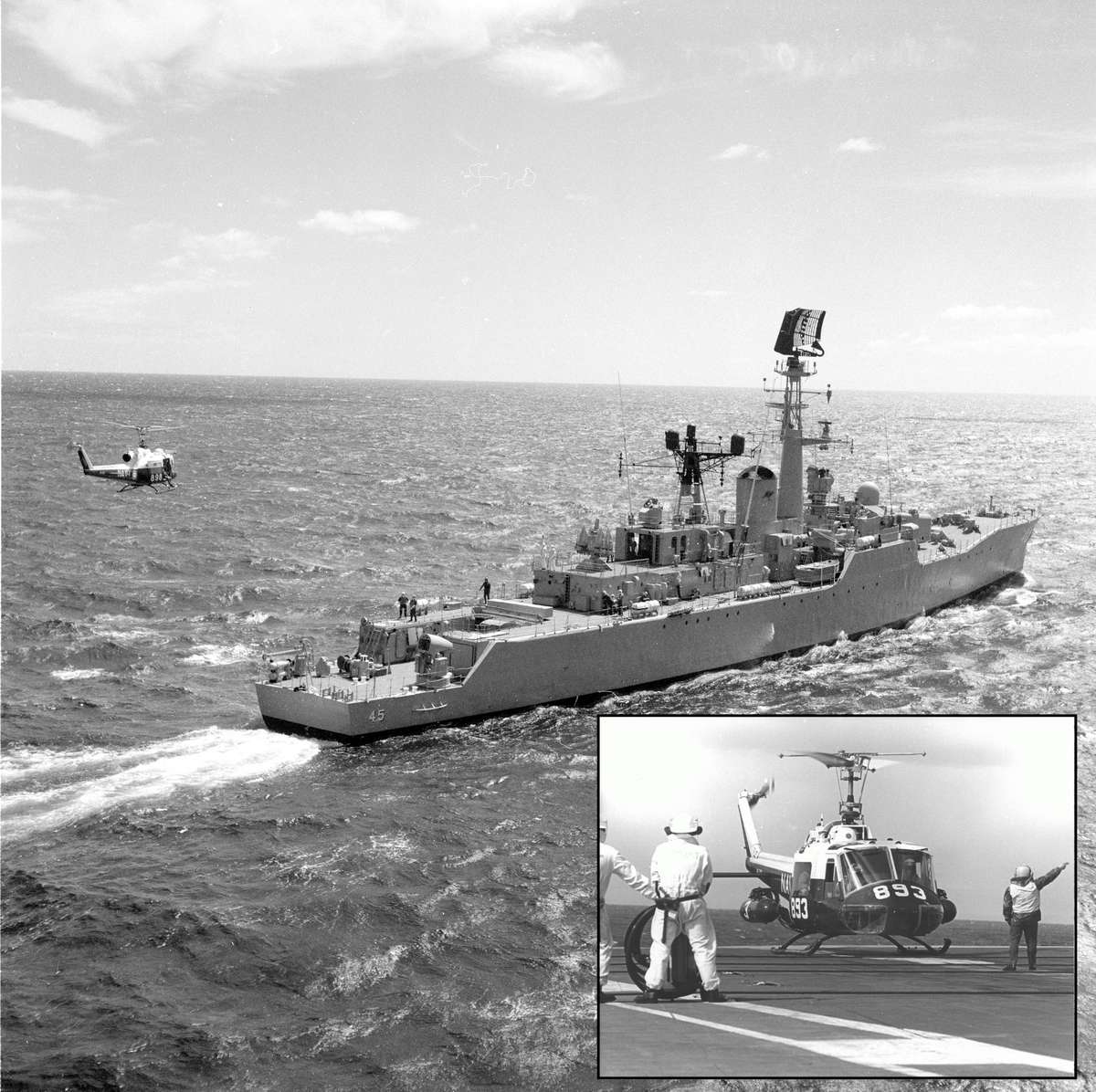

Below: With its relatively rigid skidded undercarriage, teetering rotor head and lack of marinisation, the RAN’s UH1-Bs were never meant to be embarked. They were widely used for ‘hash and trash’ trips to ships’ decks, however, mostly delivering or collecting passengers, mail or stores. Occasionally, if the weather was benign, they would land on deck (inset on HMAS Melbourne, below). More usually they simply used the winch. In the main picture below, 898 makes an approach to HMAS Yarra’s quarterdeck, where a small deck party awaits her.

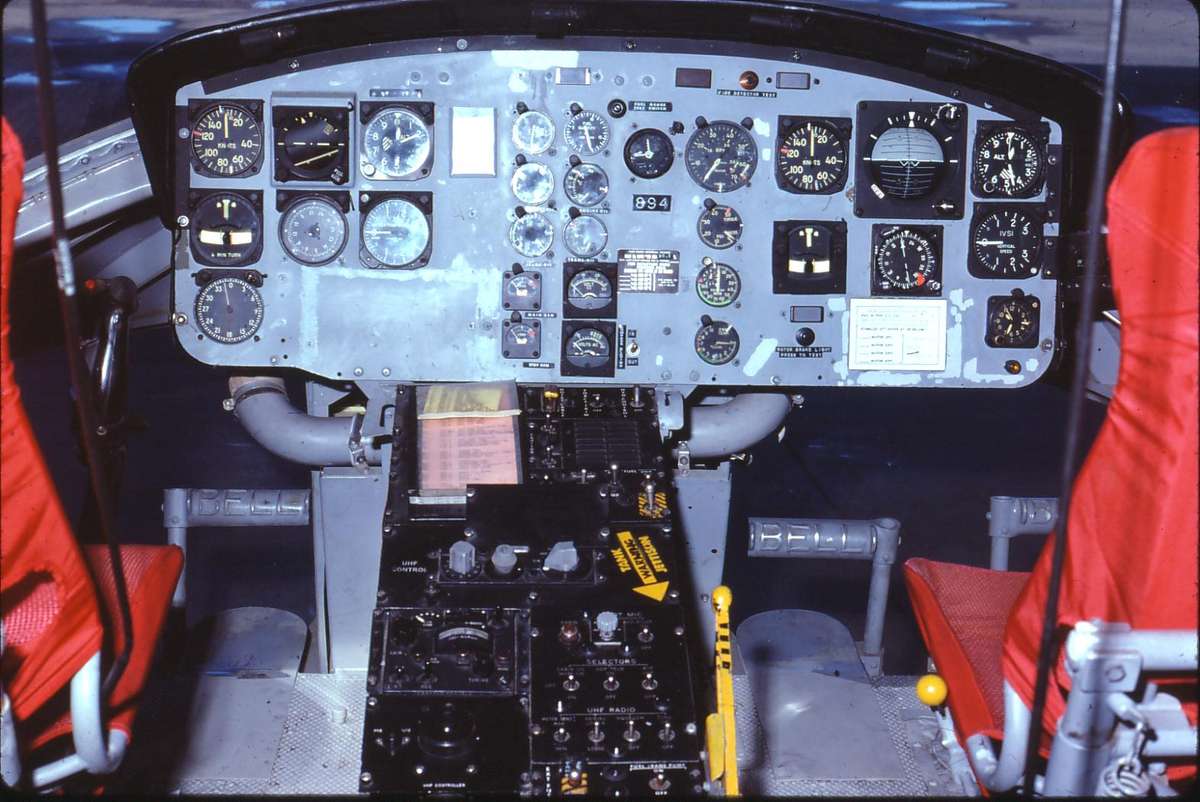

Left. Navy thought it had lost its third Iroquois on 25 November 1970 when 894 (N9-3102) ditched in Jervis Bay – but although it submerged the aircraft sustained minor damage and was recovered intact. Hawker De Havilland at Bankstown carried out a strip and re-build. During this program structural repair work was necessary, so 894 was transferred to Bell Helicopter Australia Brisbane. It re-entered service in August 1972.

In August 1973 major corrosion was discovered in the rear cabin bulkhead and fixed flooring, resulting in withdrawal from service for repairs at BHA Brisbane. During this repair the internal fuel capacity was increased by the installation of a “Charlie” model fuel cell. This increased internal fuel capacity to 1600 pounds giving a flight duration of three hours. The aircraft re-entered service again in December 1974.

In the late ’80s corrosion again became a major problem and it was decided to withdraw the aircraft from service with effect from October 1988. Photo by Stephen Wood. (Disregard the printed date on it.)

The aircraft is now mounted on a pole in the township of Nowra.

AIRCRAFT LOSSES

Over the life of the Iroquois three of the seven aircraft were written off, while the remaining four survived to retirement to museums or display poles. At the time of preparing this page two are in the process of restoration to flying status. You can see a list of the Cat 4/5 accidents here, with links to further information.

Above right: These two Iroquois take a break from their primary role to help out the Army School of Parachuting. Trainees would normally use a RAAF Caribou or Hercules for their jumps, but the occasional dispatch from an RAN helicopter provided both variety and additional experience.

Right: An Iroquois flies past Mt. Ngauruhoe in New Zealand in April of 1973, one of three (893/4/5) engaged in Exercise COLD KOALA at the NZ Army Training Base at Waiouru. They were ferried aboard HMAS Sydney for the 18 day exercise. Then LEUT Max Speedy was CO. His recollection of this event and of HC723 more generally, can be read here.

Below. Although it was used for many utility roles, the Huey’s ‘bread and butter’ was training pilots and aircrewmen. Here, an Iroquois is practicing scooping up a ‘survivor’ in a Billy Pugh net and then transferring him to one of the small Torpedo Recovery Vessels based out of HMAS Creswell. The Billy Pugh was designed to retrieve bodies or unresponsive survivors from the water but it was seldom used as SAR Divers were a far better option. It was, however, a great training aid.

Right: Another role never far from reality was for Search and Rescue, or Medevacs. Over the life of the aircraft the individual tasks carried out by the Squadron would be too numerous to mention, but every one of them either saved a life, or added value to it in some way. Here, a seriously ill child is transported from Moruya to Canberra – a four hour trip on a twisting road transformed into a life-saving one hour flight. Regrettably the crews seldom got to hear of the outcome of such work – it would be interesting to know whether this young soul survived, and if so, how they are now going in their middle age.

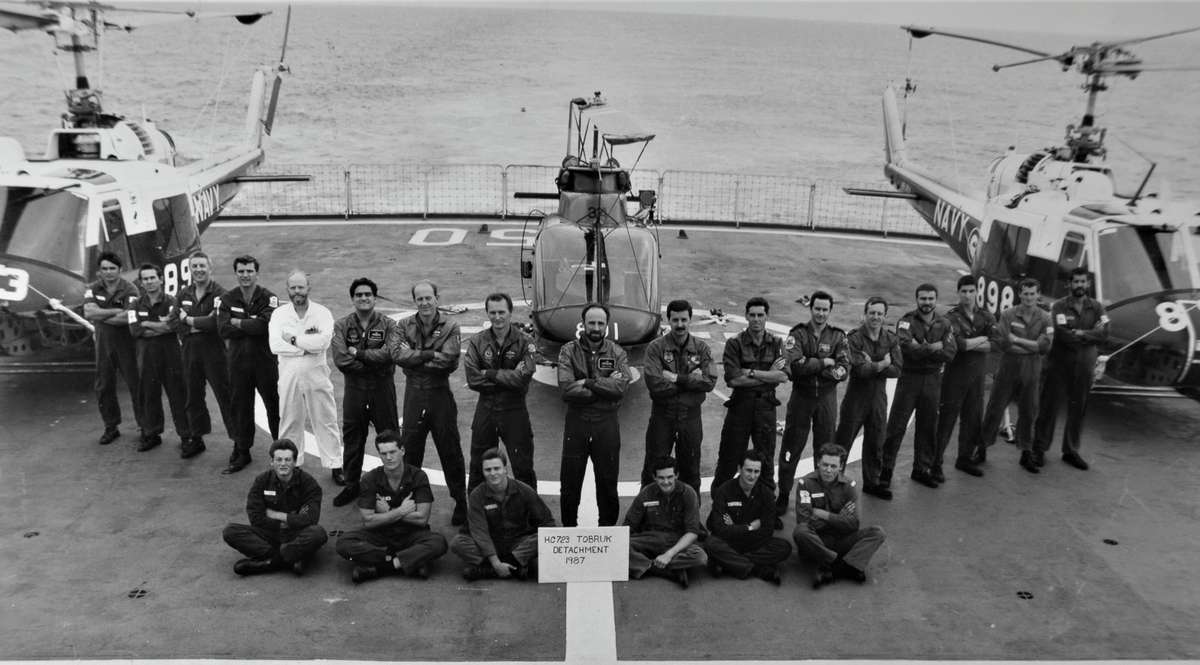

Below. One of the few occasions when the Iroquois did embark – and arguably the only time they were used for Operational Service, was for ‘Operation Morris Dance’ in 1987. This was the Governments response to the 1987 Military Coup in Fiji, when elements of the RAR and Navy were dispatched to the Islands for the potential evacuation of Australian nationals should it have been necessary.

Left. HC723 Squadron’s rotary wing assets in ‘F’ hangar in 1979: Wessex, Iroquois and Kiowa. The three types were already old by then, but incredibly were only about half way though their service life. It looks like a lot of airframes, but in fact the RAN never had more than six on the ORBAT, and at one stage was down to just two. A chart showing airframe assets in any year can be seen by clicking on the image immediately right.

Below. In October 1998 Navy retired 894 (N9-3102) early. Since its immersion in Jervis Bay in 1970 it had suffered from corrosion and the discovery of yet more made it economically unviable to repair. It was donated to the township of Nowra and placed on a pole at the northern entrance to the town, not far from the bridge.

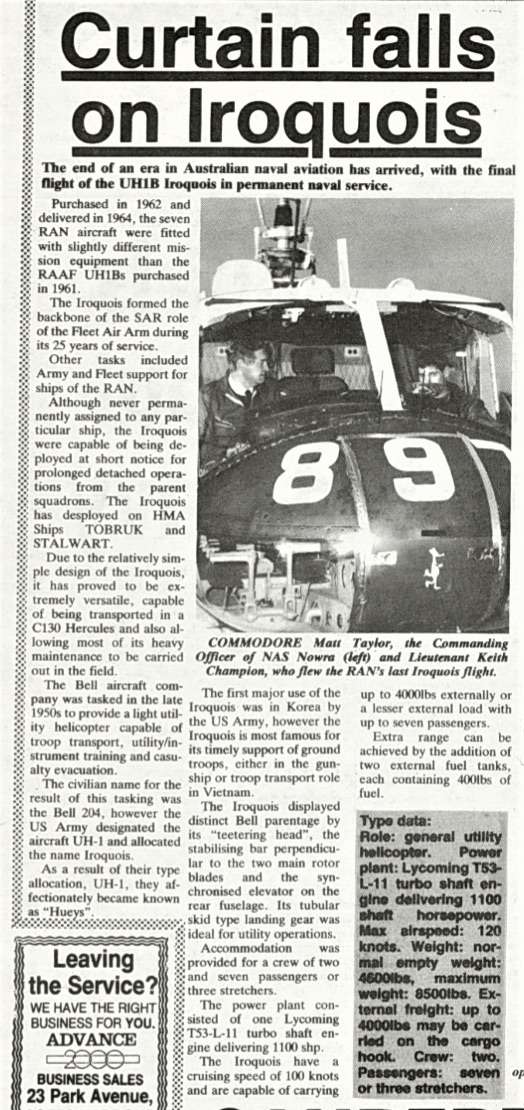

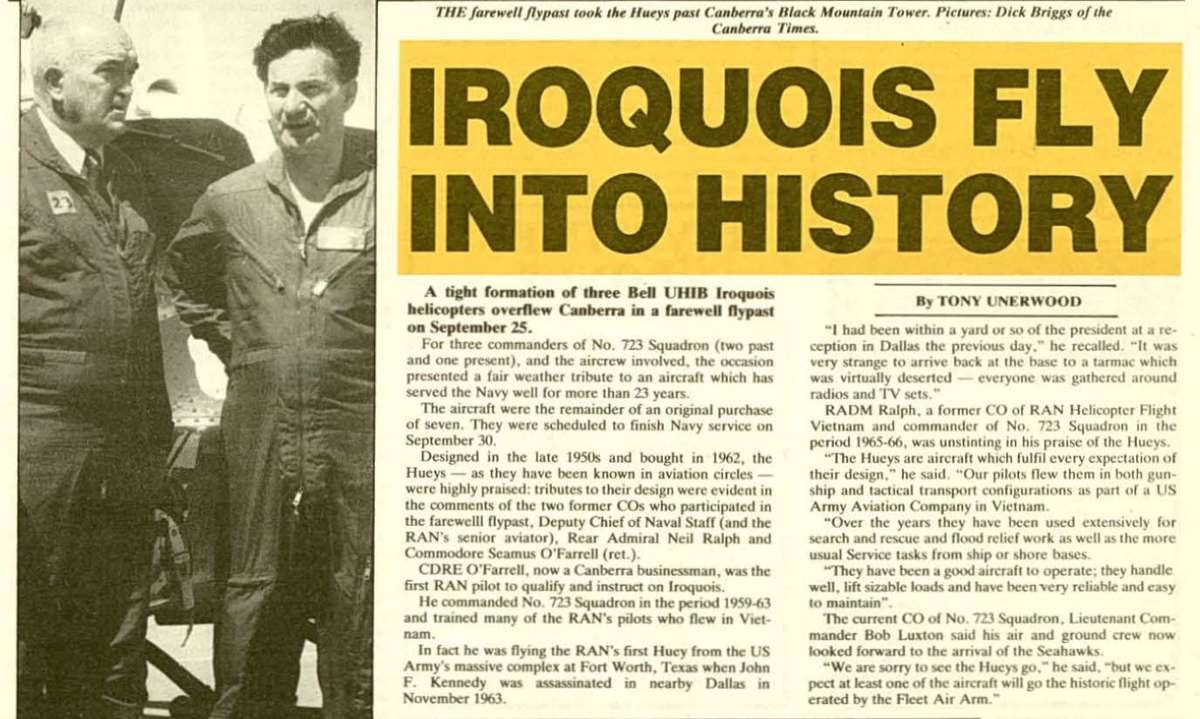

1989 marked the end of the Iroquois’ life. By then the AS350 Squirrel had taken over the training role and the S70B Seahawk had been introduced, and the Hueys were no longer viable. Like their introduction 25 years before, it was left to the newspapers to tell the story of their retirement.

But what of the remaining three airframes? Unusually, all of them survived, although with chequered histories. N9-882 found its way into the FAA Museum where it resides to this day. N9-3104 (898) looked to have the brightest future: it was given to the RAN Historic Flight where it was maintained in impeccable flying order, appearing regularly at airshows and other events (below). The Flight was disbanded in 2009, however, and its aircraft deteriorated over the next ten years or so, until they were finally sold by tender. The two Hueys fared better than some, however, as they had been stored under cover.

The Historic Flight’s inventory was purchased by the Historic Aircraft Restoration Society in 2018 and the two Hueys were transferred to Air Affair’s hangar on the western side of HMAS Albatross, where they are gradually being restored to flying condition. Unsurprisingly, 898 will probably be the first to fly but at the time of writing this article no date is available. (Main photo below: HARS Iroquois in the Air Affairs hangar in mid 2020. (HARS image)

Note by Webmaster. These pages would not have been possible without the enthusiastic support of many people who gave of their time and/or donated photographs or text to assist. My particular thanks go to Max Speedy, Ian “Tiny” Warren, Ray Godfrey, Greg Morris, John Macartney and Geoff Ledger. I’m also indebted to Kim Dunstan, who is the driving force behind so many of our Heritage articles and who keeps me honest.

Most of the photographs used in these pages are from the internet or ‘hand me downs’ with no source reference. If you think we have used one without permission, please use the “Contact Us” box at the foot of the page to let us know.

Finally, articles like this are never finished! There are so many Iroquois stories out there – please, help us build on this one and capture others. History is easily forgotten and so hard to resurrect once it is, so now is the time!! Marcus Peake, Aug 20.